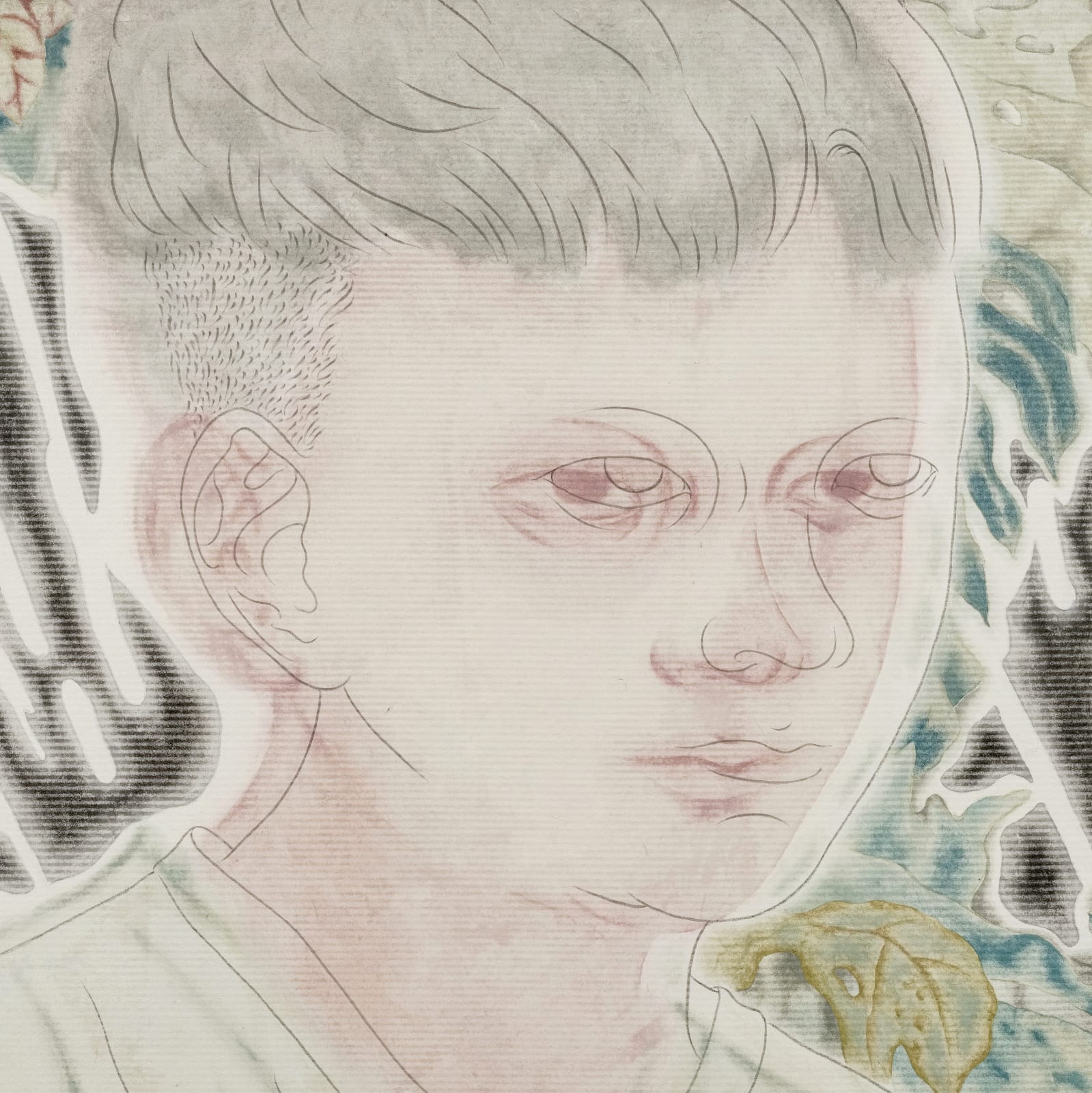

Su Huang-Sheng 苏煌盛

Landscape 17 风景之十七, 2020

Mineral pigment and ink on paper

矿物颜料、墨、楮皮纸

矿物颜料、墨、楮皮纸

30 7/8 x 55 3/4 in

78.5 x 141.5 cm

78.5 x 141.5 cm

Copyright The Artist

In Landscape 17, Su uses his fine gongbi brushlines to limn the outlines of his young male subject. Is this a self portrait? Su doesn't say as much but states...

In Landscape 17, Su uses his fine gongbi brushlines to limn the outlines of his young male subject. Is this a self portrait? Su doesn't say as much but states instead that a youth in his or her teens or early twenties represents a person at that most formative stage of development, emerging into his or her own identity as an adult individual. It is something all people can identify with and thus represents not just him. The traditional gongbi mode of figurative painting inherited from the Song uses ink outline (rendered with a stiff, fine brush) followed by color, wash infill. Here, Su deploys both traditional approaches—ink line followed by color fill—with tremendous technical dexterity but instead of combining the two to form a coherent visual illusion, he spatially separates or offsets the two to create a dissociated visual image. He recalls happening upon this visual effect when visiting a classmate who was working on a woodblock printing project. In traditional Chinese and Japanese woodblock print, the Song gongbi technique is reproduced using multiple printing blocks: one carved woodblock impresses the ink outline of the painted forms and subsequent woodblocks impress the color fill (one carved block per color). Proper registration or alignment of the multiple woodblock impressions is necessary to achieve a coherent, illusionistic result. Alignment errors, however, are not uncommon and on this day, Su stumbled upon a discarded, mis-aligned print. Through its “failure,” the discarded print struck a dissonant chord with Su’s own gongbi painting practice drawing explicit attention to the painter’s long-accepted, never-questioned traditionalist formulation of brush outline and color-wash fill. At the same time, Su felt a deep, psychological resonance with this same image—a sense of double vision, of personal dissociation, of seeing oneself from the outside or of a separation between one's inner self and one's social self. This productive nexus between visual experience, historical artistic practice, psychological phenomena and personal identity is the engine that drives Su’s artistic practice.

在作品《风景之十七》中,苏煌盛用细腻流畅的工笔线条勾勒出青年男性的轮廓。这是一幅自画像吗?艺术家未作过多说明,但表示十几岁或二十岁出头的年轻人,能代表人生成长过程中最重要的塑造阶段,开始以一个成年人的身份出现。这一点在所有人身上都能得到体现,并不只是艺术家本人。宋代传统的人物工笔画技法,是先以硬毫勾勒轮廓,再用颜料和水墨填色。在这幅作品中,苏煌盛就运用了这种先勾后染的传统方式,技法上非常娴熟。但艺术家的勾线和着色没有形成连贯的视觉效果,而是从空间上将两者分离或偏移,创造出一种错位的视觉图像。据苏煌盛回忆到,他是在拜访一位在做木刻版画的同学时,偶然发现了这种视觉效果。在中国和日本传统的木刻版画中,宋代的工笔技法是通过多版套印来呈现:先在一块板上铺墨印出结构轮廓,其余套印木板分色,每块板只印一种色彩。多块木版需要准确对版,才能产生连贯的视觉效果,但对版失误也并不罕见。这一天,苏煌盛就偶然发现这样的一个对版失误的废弃版画。这个”失败案例”与苏煌盛自己的工笔画实践产生了一种反常的共鸣,让艺术家开始反思自古被人们接受、从未被质疑的传统勾线和染色模式。同时,苏煌盛对这个意象产生了深刻的心理共鸣。这是一种双重的视觉感、个人分离感和从外部看到自我的感受,或是一种内在自我和社会自我之间的分离感。正是这种视觉体验、历史艺术实践、心理现象和个人身份之间生发出的关系,成为了苏煌盛艺术实践的动力。

在作品《风景之十七》中,苏煌盛用细腻流畅的工笔线条勾勒出青年男性的轮廓。这是一幅自画像吗?艺术家未作过多说明,但表示十几岁或二十岁出头的年轻人,能代表人生成长过程中最重要的塑造阶段,开始以一个成年人的身份出现。这一点在所有人身上都能得到体现,并不只是艺术家本人。宋代传统的人物工笔画技法,是先以硬毫勾勒轮廓,再用颜料和水墨填色。在这幅作品中,苏煌盛就运用了这种先勾后染的传统方式,技法上非常娴熟。但艺术家的勾线和着色没有形成连贯的视觉效果,而是从空间上将两者分离或偏移,创造出一种错位的视觉图像。据苏煌盛回忆到,他是在拜访一位在做木刻版画的同学时,偶然发现了这种视觉效果。在中国和日本传统的木刻版画中,宋代的工笔技法是通过多版套印来呈现:先在一块板上铺墨印出结构轮廓,其余套印木板分色,每块板只印一种色彩。多块木版需要准确对版,才能产生连贯的视觉效果,但对版失误也并不罕见。这一天,苏煌盛就偶然发现这样的一个对版失误的废弃版画。这个”失败案例”与苏煌盛自己的工笔画实践产生了一种反常的共鸣,让艺术家开始反思自古被人们接受、从未被质疑的传统勾线和染色模式。同时,苏煌盛对这个意象产生了深刻的心理共鸣。这是一种双重的视觉感、个人分离感和从外部看到自我的感受,或是一种内在自我和社会自我之间的分离感。正是这种视觉体验、历史艺术实践、心理现象和个人身份之间生发出的关系,成为了苏煌盛艺术实践的动力。