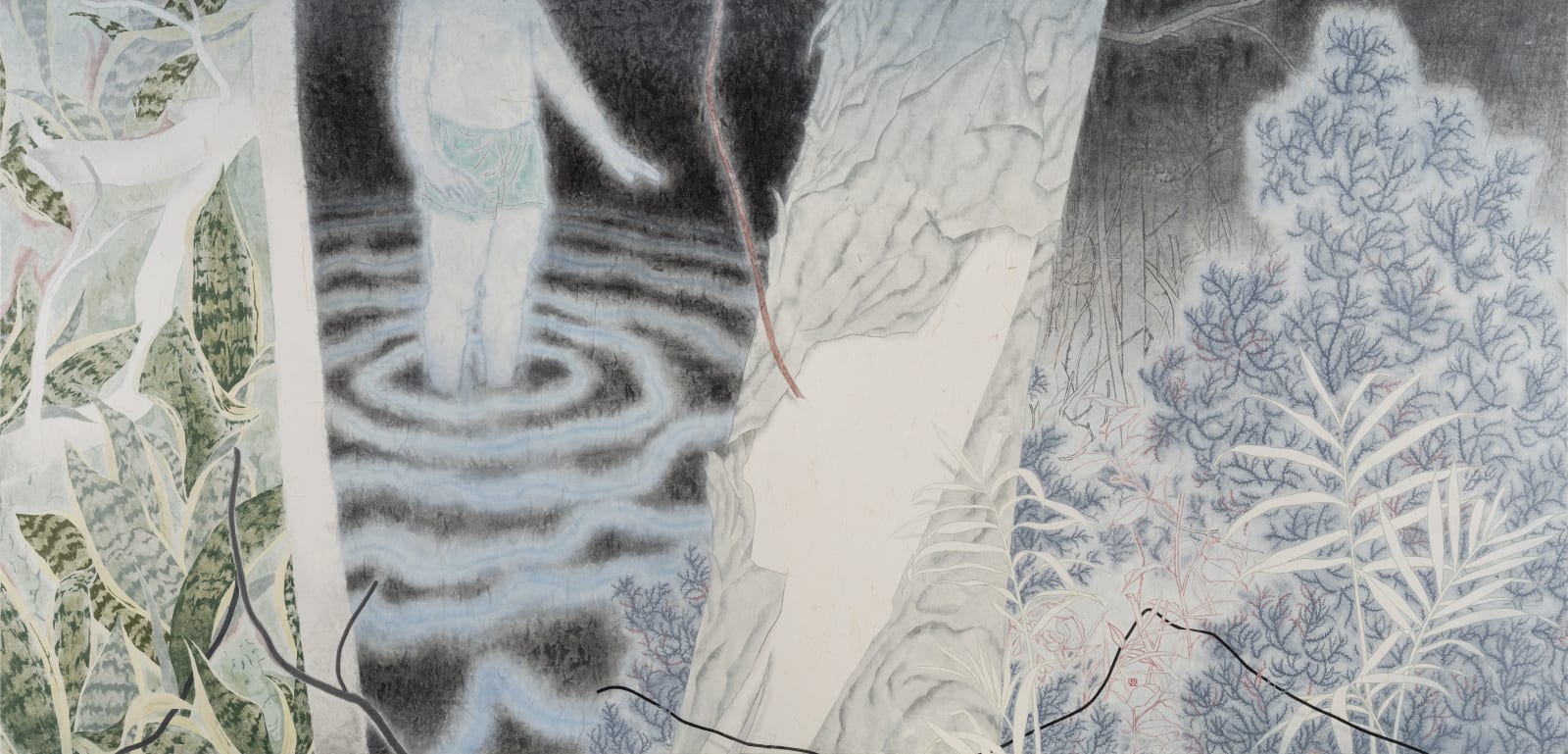

Su Huang-Sheng 苏煌盛

Landscape 11 风景之十一, 2017

Mineral pigment and ink on paper

矿物颜料、墨、麻纸

矿物颜料、墨、麻纸

35 3/8 x 74 3/8 in

90 x 189 cm

90 x 189 cm

Copyright The Artist

In Landscape 11, Su draws from his embodied, perceptual experiences of the local forested landscape near his home. Su’s unidentified young male protagonist makes another appearance this time as a...

In Landscape 11, Su draws from his embodied, perceptual experiences of the local forested landscape near his home. Su’s unidentified young male protagonist makes another appearance this time as a headless bathing figure. How an artist manages experience, movement, space and depth is a central, historical concern in Chinese landscape painting. Unlike Western drawing and painting which solves these problems by adopting illusionistic point perspective during the Renaissance, Chinese landscape painting adopts a moving perspective that shifts as one’s eye moves through a composition. By the Song, three methods of depicting a moving perspective were codified in the “Three Distances” or san yuan: “Level Distance” or pingyuan, “Deep Distance” or shen yuan and “High Distance” or gao yuan. Su, here, is actually employing two of these methods: “level distance” in the depiction of space (across the level surface of the water) around his bathing figure and “deep distance” in the depiction of forest trees layered in depth one behind the other. Between these two passages we are confronted with a foreground tree trunk that simultaneously divides and joins these two compositional spaces and exiting the composition to the far left we are confronted even more closely with a dense wall of green foliage. Such shifting treatments of space are characteristic of the traditional, long, horizontal handscroll format and so Su’s adoption of this approach here is well grounded within historical artistic practice. What is entirely new, however, is the close-in, first-person perspective that Su conveys in his shifting treatment of space. In the traditional handscroll, the composition’s narrative and its encompassing space unfolds as if seen from an omniscient perspective: scholars and their servants travel along mountain paths, settle into a mountain retreat, steep tea or drink wine, recite poetry or play the zither. We watch the events unfold in time and space as our eve visually navigates across the handscroll’s long horizontal composition. In Su’s painting, however, the viewer’s perspective is not from an omniscient point of view outside of the composition but from within the composition, as if we ourselves are walking through the forest, hiding behind a tree trunk, pushing through a thicket of leaves. In the long history of Chinese painting, this first-person perspective is entirely missing from traditional landscape composition. By working from his own personal, perceptual experience of his natural surroundings, Su has created a completely original way of handling space: one firmly grounding in traditional painting practice and yet visually completely fresh.

作品《风景之十一》的创作灵感来源于苏煌盛对居所附近当地森林景观具体的感知体验。这个身份不明的年轻男主角以隐去头部的沐浴形象再次出现。如何处理画面的体验、动态、空间和深度,是中国山水画核心的历史问题。与文艺复兴时期西方绘画采用焦点透视法解决这些问题不同,中国山水画采用的是散点透视法,画面中的观察视角在不断移动。北宋郭熙以“三远”即“高远、平远、深远”阐释了散点透视的概念。在这件作品中,苏煌盛实际上采用了“三远”中的“平远”,以湖的水平面表现沐浴人物周围的空间,和“深远”来描绘繁茂叠翠的林木。以这两种视角来观察,前景中的树干又将这两个构图空间和最左侧的一堵浓密的绿叶墙分割和联结。这种空间变换的处理方式是传统手卷的特点,所以苏煌盛的手法是基于历史的艺术实践。但他的创新在于,在空间变换的处理中采用了近距离的第一人称的视角。在传统手卷中,画面中叙事和空间的展开不受视域的限制:高士和书童沿山道徐步缓行,于山间茅庐小憩,或烹茗、饮酒,或吟诗、抚琴。长卷中目光所及之处,事件在时空中生发。但对于苏煌盛的作品,观看视角并非画外无所不在的视角,而是从画面内部出发,让观者身临其境,好似正穿过森林,躲在树干后面,推开茂密的灌木叶。在中国绘画漫长的历史进程中,这种第一人称的视角在传统的山水构图中可谓完全缺失。苏煌盛能从个人对自然环境的感性体验出发,完全独创出一种崭新的空间处理方式,它牢固根植于传统绘画实践,但带来的是绝对鲜活的视觉感受。

作品《风景之十一》的创作灵感来源于苏煌盛对居所附近当地森林景观具体的感知体验。这个身份不明的年轻男主角以隐去头部的沐浴形象再次出现。如何处理画面的体验、动态、空间和深度,是中国山水画核心的历史问题。与文艺复兴时期西方绘画采用焦点透视法解决这些问题不同,中国山水画采用的是散点透视法,画面中的观察视角在不断移动。北宋郭熙以“三远”即“高远、平远、深远”阐释了散点透视的概念。在这件作品中,苏煌盛实际上采用了“三远”中的“平远”,以湖的水平面表现沐浴人物周围的空间,和“深远”来描绘繁茂叠翠的林木。以这两种视角来观察,前景中的树干又将这两个构图空间和最左侧的一堵浓密的绿叶墙分割和联结。这种空间变换的处理方式是传统手卷的特点,所以苏煌盛的手法是基于历史的艺术实践。但他的创新在于,在空间变换的处理中采用了近距离的第一人称的视角。在传统手卷中,画面中叙事和空间的展开不受视域的限制:高士和书童沿山道徐步缓行,于山间茅庐小憩,或烹茗、饮酒,或吟诗、抚琴。长卷中目光所及之处,事件在时空中生发。但对于苏煌盛的作品,观看视角并非画外无所不在的视角,而是从画面内部出发,让观者身临其境,好似正穿过森林,躲在树干后面,推开茂密的灌木叶。在中国绘画漫长的历史进程中,这种第一人称的视角在传统的山水构图中可谓完全缺失。苏煌盛能从个人对自然环境的感性体验出发,完全独创出一种崭新的空间处理方式,它牢固根植于传统绘画实践,但带来的是绝对鲜活的视觉感受。