In 1845, Honoré de Balzac wrote a short story entitled ‘Le Chef-d’œuvre inconnu’ (‘The Unknown Masterpiece’). In the story, a young Nicolas Poussin visited a master painter, where he learned that the master had been working in secret for more than a decade to create the perfect masterpiece. When Poussin finally saw the work, he was surprised to discover nothing but confusion on the canvas. This master had been immersed in his perfect vision for a decade, but only disorder appeared in the painting. This short story is an allegory that is at times difficult to explain, but I see it as neither satirising perfectionism nor evocative of the tragic sublime. Instead, it is a fundamental metaphor. The old master in Balzac’s story sees his muse in a chaos of line and colour, and in this perfect metaphor for modern painting, the true muse is the medium of painting itself, rather than the subject or theme of his paintings. The painter’s desire to depict his soul and vision of himself bordered on madness, but that chaos hiding in the depths of a studio or an unidentifiable canvas are the ultimate secret of artistic work—these signals that come out of nowhere are traces of past existences and the manifestations of invisible realms.

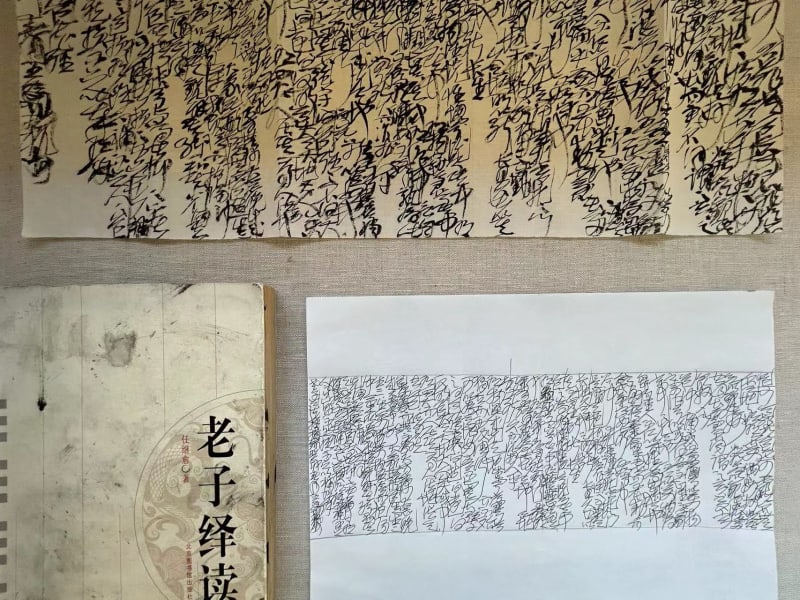

Wang Dongling’s ‘chaos script’ (luanshu) could be considered a Chinese echo of Balzac’s metaphor. In his work, we perceive signs of the dialectic between order and chaos, boundlessness and impermanence, multi-polarity and apolarity.

The closeness of Chinese calligraphy and Chinese characters led to the development of calligraphy as a unique cultural and artistic form. Michael Baxandall once said that calligraphy is a bridge connecting the two cultural systems of the textual and the visual. The imagery of calligraphy is rooted in the forms of characters. Calligraphy needs to be identified and read, even though it is also an image, the object of visual appreciation and enjoyment. Calligraphy is three-dimensional movement on a two-dimensional plane, but because the brushstrokes follow one after another in time, calligraphy could be considered four-dimensional. If we also add sound and meaning, then calligraphy is truly a higher-dimension mode of creation, shifting between mark and image, significance and manner.

The visual and the linguistic inspire one another, and text and writing shine more brightly in each other’s company—these traits are the most distinctive and moving features of Chinese culture. As writing, calligraphy gradually appears, frees itself, and grows over time, and writers become fluid and expert through hours of writing. Only this fluidity can produce change, and only change can produce pleasure. When writing to the point of pleasure, the writer may let his brush roam free. He finds irrationality and joy in every stroke as he forms an elusive image. Descriptive marks arise spontaneously, unforeseen and irreplicable.

Chaos stands relative to order. In the ancient Greek cosmos, order came first, and without order there was no cosmos. In classical Chinese philosophy, represented by Laozi’s Dao De Jing, presence and absence, chaos and order are the two poles in a nurturing, complementary dialectic. ‘He who causes disorder will maintain order’ is a classic example of this dynamic. Chaos script (luanshu) and writing chaos (shuluan) is the resistance to and dismantling of the orderly canon of calligraphy. Chaos script opens a free yet unruly space: Chaos script has no characters, and when divorced from text, writing becomes indecipherable, and the condition of writing becomes central. Chaos script has no writing, and when divorced from the canon (laws and methods), writing becomes pure action, and the act of writing becomes central. Chaos script has no imagery, standing apart from all supportingimagery and all graspable concepts. Writing becomes simple ink, markings, and traces, and the physicality and emotional tenor of the writing becomes the centre of everything. Wang’s chaos script crystallises action. When that action stops, the state and meaning of that movement linger. This state of action is a dance that arises when the mood strikes. The impulse to write chaos stems from writing in an uninhibited state of disorientation and overwhelm. In the state of writing generated by the dialectic between chaos and order, a calligrapher loses himself yet finds contentment.

In the Dao De Jing, Laozi wrote, ‘In dark half-lit, a likening; / In light half-dark, forms visible.’ As I understand it, the ultimate goal of Wang’s chaos script is returning to zero. After removing the obstacles of word, writing, and imagery, chaos script leads to an evolution and a kind of primitive mimesis. With chaos script and writing chaos, he mimics and develops the mutability and ambiguity that Cangjie created when he invented Chinese characters.

From one to zero, from multi-polar to apolar, from the indescribable to the nameless—the way of chaos script moves toward a nameless imagery or toward marks without forms that seem to respond to the primordial chaos of the Big Bang that the great Cambridge physicist Stephen Hawking described.