Wei Ligang is a larger-than-life character, a person who could characterize his birth and subsequent existence in a grandiose and supremely fanciful way thus: “In 1964, the Year of the Dragon, Wei Ligang fell like lightning from Planet No. 7 to the Earth. He always remembers the formula for the truth and the magnificent radiance of that place—his home planet.”[1]

Wei Ligang’s artistic expression is a unique synthesis of the cerebral and the tangible, of the elite and ethereal with the alien, the common, and the natural. To find inspiration for calligraphic form in ancient Egyptian writing, the wheels driving massive machinery, bones, or a tree branch, may seem strange, but it makes perfect sense. Our sense of beauty, of what feels right, is based in our experience of nature. We are part of nature, although this is often forgotten. Evolving over millions of years, in tandem with the evolution of plants and animals and the creations of animals—their homes and paths— human beings saw their forms as essential expressions of the natural and beautiful world they inhabited. Humans internalized these forms and, when they began to build and create, these forms infused their creations.

Nature has a common set of proportions that inform the design of flowers, trees, leaves, and so on. We find these same proportions in the great works of art, called by the classical world the golden mean. The golden mean shapes architecture and can be found in painting compositions and in the composition of Chinese calligraphy. Furthermore, Chinese calligraphers long recognized the connection between nature and art, particularly as China’s writing system began as pictographs. Later there came to be terms to describe certain brushstrokes such as wuluoheng, meaning drips down a wall. And there is a form of calligraphy called bird writing.

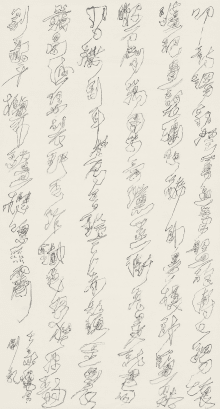

Wei Ligang has taken this knowledge and pushed it to create the basis of an individualistic calligraphic form. Although it can appear distant from tradition, traditional skill derived from years of practice underlies his often surprising oeuvre. He loves gorgeous colors, combining backgrounds of gold with lapis blue flowers, or broad sinuous ink lines, or dry-brush characters with fanciful forms of birds, dwellings, and all manner of fanciful creature. A recent innovation is to use copper metal strips as the background to landscape painting.

Wei Ligang hales from Shanxi, the home of the great calligrapher Fu Shan (1607-1684). Fu Shan was an important witness of the tumultuous Ming-Qing change, acting as an important theorist of the time, and developing a new kind of calligraphy. Wei Ligang lives in a similar time of change and, like Fu Shan, has produced a grand and flourishing new kind of calligraphy and theory. He is particularly interested in educating enthusiastic would-be calligraphers, whether they be artists by profession, or by avocation, or simply fiercely curious. Every year he devotes some weeks to teaching a class of such people, and opening their eyes to the generally ignored forms around them, seeing them as a pathway to calligraphic creation.

[1] Wei Ligang. Universal Things Examine. Beijing: Beijing 3 Gallery, 2016. P. 37.