Most people who are familiar with Li Jin’s oeuvre know of what we can now refer to as his “middle period, ” a period of lush colors and succulent washes, rendering quirky homages to food and to other pleasures of the flesh, peopled with humorous figures—including self-portraits—who are variously feasting, bathing, posing amid flowering bushes, and eyeing one another.

For many years I have been talking with Li Jin about his painting, and where he would like it to go. He has had a pent-up yearning to simplify his palette to the extreme: he wished to paint in ink alone on paper. And of course, to accompany the shift in medium, it follows that there would be a change in subject. Li Jin had spent so many years thinking about this change, that when it finally came it was full-fledged. In just a few months, he already has poured enormous energy and thought into his new oeuvre.

Having been a master of all things to do with color, of color blending, of color contrasting, and so on, Li Jin now puts those exquisite sensitivities to the service of ink tones. Ink has long been described as having “five colors”—Li Jin makes this vibrantly clear. There is such a range of ink tone subtleties, it seems that perhaps the many years of working with color have given Li Jin extra sensitivity with the shades of ink. The new subjects of Li Jin’s paintings include food and people, as before.

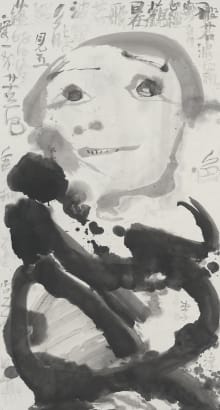

We are led to appreciate the food in a new way: a succulent piece of meat looks just as gorgeous and tender in ink as it would have looked in colors, but the ink form has an enticing ambiguity: it could perhaps be a section of landscape. The large paintings of radish or cabbage have a presence, and even personality, that is only possible with monochrome ink. The ink figures show a different aspect of humanity than Li Jin’s earlier colorfully rendered figures do. This is the more spiritual side: figures who are exposing their insecurities, figures resembling lohans, ascetics, somewhat subdued self-portraits, and so on. Li Jin’s ink brushwork is powerful, and at this point in his career he is in masterful control. With larger, specially made brushes, he works in a daring daxieyi style, with large sweeps of brush and ink—sometimes dry, sometimes moist, sometimes both together. The superb brushwork brings the subject alive. We become aware of the language of ink, and the fresh direction in which Li Jin has taken it.

In the 1980's and 1990's, Li Jin travelled to Tibet in search of an authentic life and a primal connection to nature. There he was inspired to paint aspects of daily life, as well as paintings of ink figures that are eerily reminiscent of his new ink series. Considering the early, Tibet period, and the new ink period works together, we find there is a very solid thread of continuity running through his career, and we gain a holistic view of Li Jin the artist, as well as Li Jin the thinker.