|

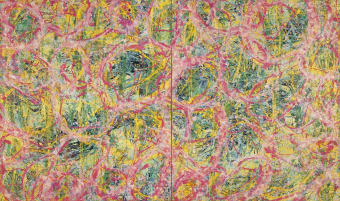

In the Zoon-Dreamscape series, Huang Zhiyang 黄致阳 expands his language of brush and ink to include pure gestural abstraction in the application of color (fig. 1).

Instead of choosing to use the dilute, translucent vegetable pigments favored by the traditional literati painters or the modern synthetic colors favored by the American Abstract Expressionists, Huang employs the vibrant ground mineral pigments of the religious mural painters of the Tang dynasty (618-907) and earlier. Earth and mineral pigments are made from naturally occurring minerals–such as malachite, azurite, lapis lazuli, and various metal oxides. Instead of the artificial colors made possible by modern synthetic chemistry, one can think of mineral pigments as the natural colors of the earth (fig. 2).

Huang dilutes these pigments with binders-to create translucent layers of vivid color- and with white acrylic-to create softer, opaque shades and hues. He then applies these colors, layer upon layer, with a round Chinese calligraphy brush or 毛笔 maobi. Although there is a spontaneous quality to Huang's brush gestures, they are not at all random and reflect, instead, a deep connection between his state of mind, his feelings and their bodily expression through his brush.

As his title for the series suggests, Huang is painting not a physical realm but a mental one. This is the world of sense, perception, feeling, emotion, memory and consciousness. Color, in almost every psychological and spiritual tradition, carries with it symbolic meaning. Among the most highly cultivated of these systems are Indian yoga, Hindu tantra, Buddhist tantra, and Daoist neigong. In the tantric systems for example:

Steeped in the color language of the ancient Buddhist muralists working at sites such as Dunhuang, Huang's use of color suggests a functioning of our spirit, mind, feelings and emotions much deeper than first meets the eye (fig. 3 and 4).

In the Zoon-Dreamscape series, however, Huang is not only working in color; rather, he always retains one layer-whether on top, below, or somewhere in between-of pure, black ink (fig. 5 and 6). Furthermore, the brushwork and forms of this layer are drawn from the same vocabulary of biomorphic images as his Zoon-Beijing Bio series. Unlike the West where, after Descartes, we separated the realm of the transcendent mind from that of the physical body, the Eastern and South Asian traditions embedded the psychological, mental and spiritual in the body. When yogis and Buddhists mediate, they calm the mind through breath and transform breath, prana or 气 qi through bodily energy centers called chakras or 丹田 dantian. We cannot but experience the world and ourselves except through our bodies; although we are conscious beings, our experience of consciousness is always embodied. So too, Huang's realm of sense, feeling, mind and spirit is inseparable from its organismic origins-mind or consciousness emerges from body or co-emerges with it.

In titling this work Zoon-Dreamscape (fig. 7), Huang draws our attention not only to the organismic origins of consciousness but also its dream-like or illusory nature. In the Buddhist view of the mind, the reality that we experience through our senses, feelings, emotions, and memories is a self-constructed illusion; even our sense of self is no more real. Liberation from the self-imposed bondage of our "selves" is won by realizing the dream-like nature of this illusion. When Huang paints for us his sense perceptions, his feelings, his emotions, and his memories, he draws our awareness to the artistry involved in such constructions. If we could only realize how we are all, ourselves, artists in this very same way, enlightenment might not be far off. |

Huang Zhiyang: Zoon-Dreamscape

Craig Yee