In one of the “Miscellaneous Chapters” of the Zhuangzi, Confucius attempts to convince a robber named Zhi to submit to the rule of Kingdom Lu. Zhi responds by dismissing the Confucian paragons Boyi, Shuqi, Shentu Di, and Wu Zixu, who sacrificed their lives to preserve their integrity and loyalty for their countries, as unnatural and hypocritical. Confucius ultimately escapes from Zhi’s withering questions and threats.

The lives of those Confucian paragons are documented in pre-Qin texts, but Zhi mentions alongside them a certain Weisheng 尾生 whose first appearance in literary history seems to be in the Miscellaneous Chapters, which were likely compiled during the Qin and Han dynasties. Even more jarringly, Weisheng’s supposedly self-sacrifice was not for any moral or patriotic purpose, but was rather a personal tragedy:

Weisheng and a woman agreed to meet under a bridge. The woman did not come. As the water rose, [Weisheng] refused to leave. He died embracing one of the pillars of the bridge.

Told in just a few words, Weisheng’s story inspired the imagination of writers throughout history. Weisheng, whose name means “last born,” was probably a young man. Certain that the woman he loved would meet him under the bridge as they had agreed, he ultimately drowned holding on to a pillar. Did they have to meet under a bridge because their relationship was forbidden? Did the woman not requite his love, or could she not come for other reasons? The image of Weisheng’s drowning is a tragic parody of a lover’s embrace. A sudden flood is an appropriate figure for desire and evokes the legend of Princess Mi’s drowning in Luo River and becoming its Goddess, inflecting Weisheng’s story with romantic melancholy.

In literary history, apart from Daoist and Confucian philosophical discourse, Weisheng’s “embrace of the pillar” soon became a symbol of faith and undying love. The Yutai xinyong of the Southern Dynasties period, the third comprehensive poetry compilation after the Classic of Poetry and the Songs of Chu, contains the following poem: “In the morning I ascend the bridge over the ravine / And lift my dress to gaze towards whom I miss / How can I gain the faith of the embrace of the pillar / With the blazing sun as my witness?” Other examples include a couplet by the Tang poet Li Bai and a line in the Ming-dynasty play Peony Pavilion by Tang Tianzu. The latter combines a reference to Sima Xiangru’s inscribing a bridge to announce his ambition with Weisheng’s story, whose tragic tone is entirely lost.

Although Weisheng does not appear in the Confucian classics, the Analects refer to a Weisheng Gao 微生高 and a Weisheng Mu 微生亩 [wei 微 and wei 尾 being homophones of different tones]. Ban Gu of the Western Han period lists Weisheng Gao 尾生高 as someone regarded by Confucius as morally deficient. Lu Deming of the Tang, when annotating the Robber Zhi chapter, connects these two Weishengs. During the Ming Dynasty, Zheng Xiao and Jiao Hong again refer to Weisheng Gao and Weisheng Mu of the Analects as the same person with the given name Mu and the sobriquet Gao, and further connects them to Weisheng of the Zhuangzi. After a millennium and a half, all three Weishengs became the same person. Who was Weisheng the tragic lover, and did he truly drown embracing a pillar? Did he even exist? We may never know.

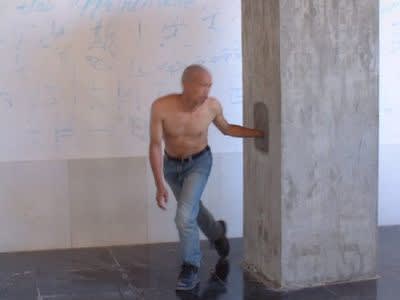

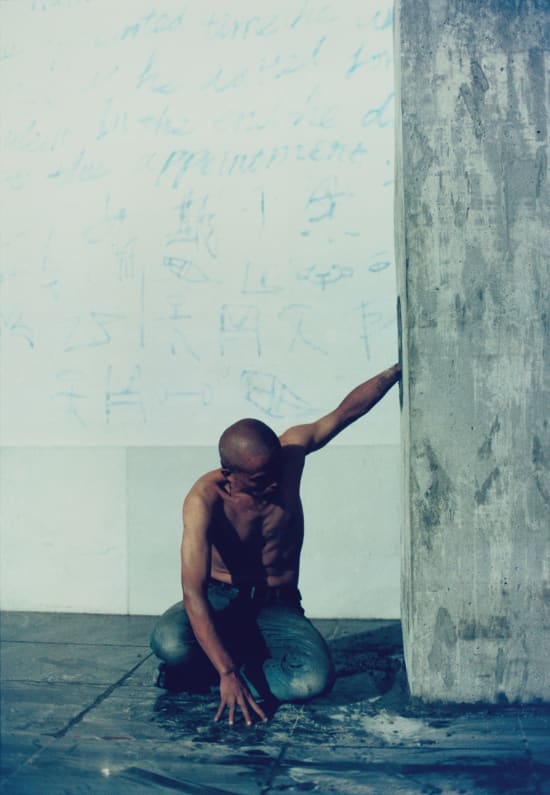

In October, 2003, He Yunchang interpreted Weisheng’s story as a work of performance entitled Keeping Promise in Lijiang, Yunnan. For 24 hours, he kept his left hand in concrete, and as it solidifed attained a solemn sculptural presence with it. He had written on a wall behind him the original text from the Miscellaneous Chapters in English, Chinese, and the script of the Dongba minority of Yunnan, seeming to invite us to consider the differences between representations of the story in different languages, including his own performance.

In a later interview, He Yunchang described the experience as follows: “I felt that I was suddenly held hostage by an immense power, a devil. I couldn’t escape however I tried, and had to bear it…” He tried to keep himself warm by moving his body. Occasionally he needed to sit and rest, but was prevented from doing so comfortably by his trapped left hand. The scenario seems to channel, across time, the fraught intermingling of fear and faith in Weisheng. In this 24-hour vigil a millennia-old story is made visceral.

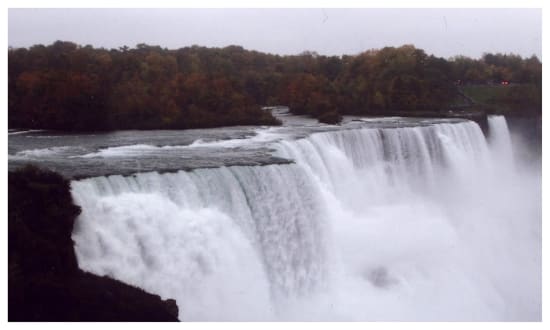

In He Yunchang’s works, water recurs as a theme and an object of resistance. In the early performance Dialogue with Water (1999), he suspends himself upside down from a crane over the river Liang of his hometown and attempts to cut it into two halves as blood flows from wounds on his wrist into it. In River Document, Shanghai (2000), he spent 10 hours moving ten tons of water of Suzhou Creek in Shanghai upstream, causing the “river to flow in reverse for 5 kilometers.” In the aborted Rock in the Niagara Falls (2005), he attempted to sit for 24 hours in the middle of the falls. Concrete—a powdery substance that paradoxically solidifies when mixed with water—is also one of He Yunchang’s favorite materials and provides an intriguing counterpoint to water’s liquidity. If flowing water is a metaphor for the passage of time and its attendant oblivion, in Keeping Promise concrete seems to stand for the persistence of truth in the face of it.

In an essay entitled Fairytales for Adults written on April 1, 2002, He Yunchang playfully describes the forgetting and misinterpretation of his own works as a sublimation of them into a higher order of truth. His absurd attempts to cut a river and move a mountain and so on, he says, may in a few centuries become legends whose truthfulness cannot be determined: “ Another thousand years go by, and the legends are somewhat altered. There once was a master who moved three mountains across 3000 kilometers with a wave of his hand; an arhat who could strike a river with the palm of his hand and split it in two, and who then slept for 30 years in the middle of the river bed…” Of course, this essay, written on April Fools’ Day, is full of the paradox and humor of self-parody and cannot be read literally.

The preceding interpretation of Keeping Faith, too, is no more than a fantasy inspired one of the images of Keeping Promise, yet another fairytale.