The calligrapher Wang Dongling, who is almost 70 years old, recently debuted a new series entitled Squiggles [Luanshu, literally "chaotic calligraphy"] at his solo exhibition at the Sanshang Museum of Contemporary Art in Hangzhou. As the title suggests, he compresses the spaces between characters and lines, allowing them to push against and even overlap with each other and creating the overall impression of formless chaos.

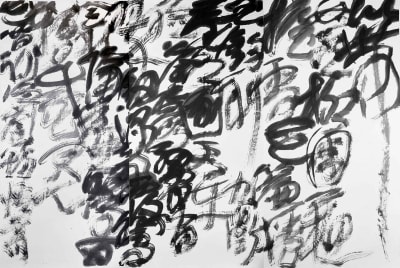

Wang Dongling Huajianci: Ganjunxin, 254×372 cm, 2015.

But this does not mean that Squiggles is haphazardly written. An active calligrapher for several decades already, Wang Dongling specializes in monumental renditions of cursive script and maintains a daily practice of copying model books. He has masterful control of calligraphiclines and of the construction and composition of characters. Even when writing "chaotically" he observes the principles of tradition. Each character is structurally sound, and each column of characters has a sense of coherence and continuity (hangqi — literally "column-breath"). Unlike traditional calligraphy, however, Squiggles flaunts the requirement for legibility in its character arrangement.

Wang Dongling himself says, "An important lesson in traditional calligraphy is that characters should not overlap, even less columns. In art history, only Xu Wei managed to eliminate the distance between columns, but even his characters didn't break into each other's space. Later, Zheng Banqiao wrote characters like "random stones covering thestreet" — some small, some large. But I completely broke what was for the ancients an untouchable principle."

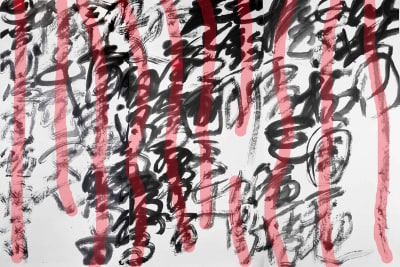

Analysis of the columns in Huajianci: Ganjunxin.

|

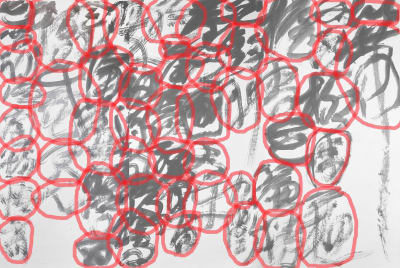

Analysis ofthe distances between characters and columns in Huajianci: Ganjunxin.

|

The characters and columns are proportionally compressed and overlap with each other.

Text(translation omitted)

似帶

如絲柳。團酥

握雪花。簾捲

玉勾斜。九衢

塵欲(暮)。逐香車。

臉上金霞細。眉間翠鈿深。欹(枕)覆鴛

衾。隔簾鶯百

轉。感君心。

花間詩。溫庭筠。悟齋。

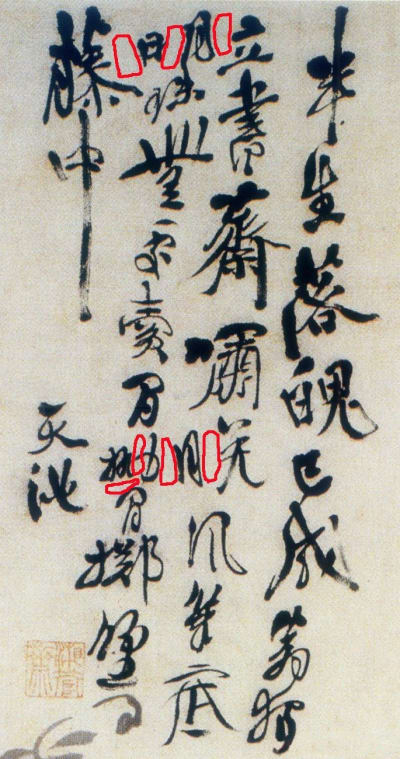

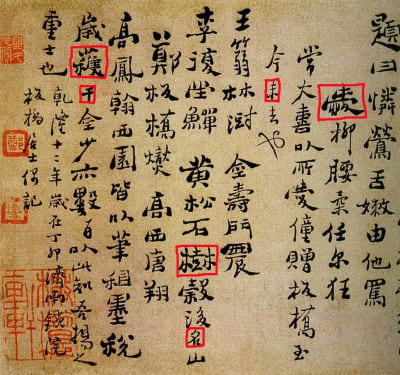

Inscription on Xu Wei’s (1521-1593) ink painting Grapes, part of the collection of the Palace Museum.

In Xu Wei's calligraphy, intra-characterand inter-character distances are sometimes identical (indicated in red), breaking with traditional compositional aesthetics. Still, the characters do not intrude into each other's space.

Detail from Zheng Banqiao’s (1693-1765) running-script calligraphy Miscellaneous Records of Yangzhou, part of the collection of the Shanghai Museum.

Zheng Banqiao's characters are like "random stones covering the street," varying greatly in size (indicated in red).

However expressively unencumbered, traditional calligraphers still meant to be read and understood. With this basic documentary function, their characters and lines could not be completely interwoven. In Squiggles, however, the textual content is no longer important. Instead the artist creates an overall visual effect, like an abstract painting. He suppresses meaning infavor formal language, which becomes the vehicle for emotional expression.

What Wang Dongling presents above all is his state of being. He accentuates the force of every stroke, character, and column, and exaggerates the changes in size, wetness, and tonality between them. Abandoning the need for legibility, he purposely weaves his characters and columns together into a gnarled, tensile, and tumultuous jumble. Unseen in traditional calligraphy, this effect recalls the paintings of Huang Binhong (1865-1955), who sought interest and order in apparent chaos [luanzhong qiuqu]. Executed in layered, interwoven brushwork, the paintings seem to represent nothing when seen up-close, but when seen from afar they disclose their "profound grandeur and nourished luxuriance" [hunhou huazi] — to quote Huang's favorite aesthetic ideal. In Huang Binhong's seemingly chaotic brushwork, objects appear skewed and disorderly on their own, but cohere into harmoniously balanced compositions. "Profound grandeur and nourished luxuriance" refer to the effect of his "broken ink" [pomo]and "accumulated ink" [jimo] techniques — that is, the mutual thwarting, layering, and buttressing of dark and light, dry and wet, long and short brushwork, resulting in passages that are at once lucidly transparent and deeply textured. Similarly, Wang Dongling's Squiggles, compositions by turns overlap densely and open into empty spaces, and his compression and interweaving of brushwork recalls Huang's "broken ink" and "accumulated ink." Wang Dongling was a student of the modern master cursive calligrapher Lin Sanzhi (1898-1989), who was a major disciple of Huang Binhong. Huang's legacy is equally important in both painting and calligraphy.

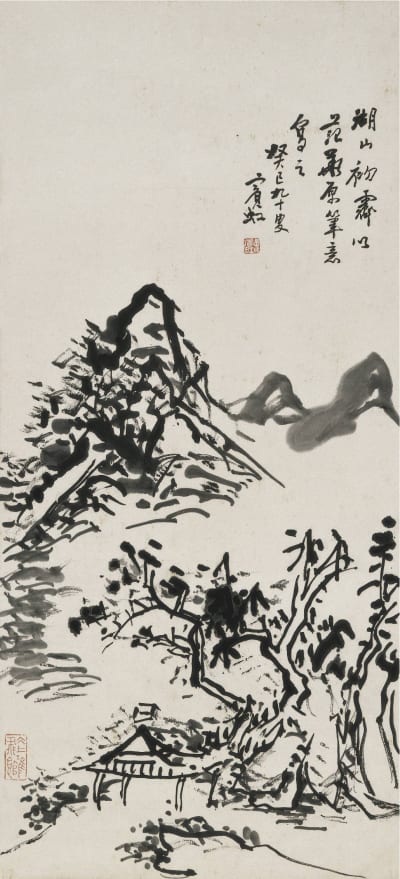

Detail from Huang Binhong’s (1865-1955) Landscape in the Style of Fan Kuan, part of the Tsao Family collection.

Not mired in verisimilitude, Huang Binhong emphasizes the interconnections between objects and brushstrokes, allowing forms to emerge organically from brushwork. Thus even his paintings are infused with the "column-breath" of calligraphy.

Detail from Huang Binhong’s painting Landscape in the Style of Fan Kuan (left) Detail from Wang Dongling’s calligraphy Huajianci: Ganjunxin (right).

The interweaving and layering of characters in Wang Dongling's Squiggles closely resembles Huang Binhong's "broken ink" and "accumulated ink" techniques.

Seen from a distance, Squiggles have an especially forceful presence, which is directly palpable regardless of the viewer's understanding of its textual content or of calligraphy history. In this series, Wang Dongling's calligraphy becomes one with abstract painting. As he himself says, "Squiggles is a new breakthrough in my artistic practice. It is a blessing from heaven, allowing me to return to nature itself."