The following interview originally appeared in Chinese on Estran (link) and is here translated and republished with Estran's permission.

Writing "Good Morning Hong Kong"

Martina Köppel-Yang [MKY]: Jo sun (“Good morning” in Cantonese). What is the motivation behind your solo exhibition for Le French May Arts Festival? What works will you show?

Yang Jiechang [YJC]: Jo sun. I will show some strange things, things not seen before by the general public.

MKY: Such as?

YJC: Works that may embarrass Hong Kongers, such as a group of paintings of pok gai [lit. “fallen on the street,” Cantonese slang approximating “fuckers”]; of boys and girls running naked; scenes of someone hanged and of animals engaged in chaotic orgies rendered in the style of the Mustard Seed Garden Painting Manual; calligraphies reading oh diu [“oh fuck”], diu [“fuck”], “Oh My God,” and “God,” executed while I was yelling the same; excited cardiograms painted with a broad brush; and silly performances like hitting a gong with my head... I think these works may sound problematic, but when you confront them face to face as art, all the “problems” are normalized and resolved. Basically my practice is all about finding possibilities for resolving problems. It's something I've always explored and been quite good at.

Mustard Seed Garden (Hung), ink, mineral pigments, silk (mounted on canvas), 2010.

Mustard Seed Garden (Landlord), ink, mineral pigments, silk (mounted on canvas), 2010.

MKY: Are the exhibits recent works?

YJC: In fact, ever since becoming an artist, I’ve always been contrarian—turning black into white, white into black. So what I did before I still do, and what I do now is inseparable from the past. Good or not, my past and present works are the same—they are all most definitely by me. The Chinese brush I use is a 5000-year-old invention. Although few contemporary artists use it, I first picked it up when I was three and have never put it down.

MKY: They are most definitely by you, but when were they created?

YJC: They are all from the present.

MKY: Aren’t there older works?

YJC: To me time is transparent. A single brush stroke is ten millennia. (Laughter)

MKY: But you didn’t create all the works at the same time.

YJC: In my Paris studio, I always have on display a pair of paintings I created not long before my graduation from the Chinese painting department at my university [the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts]: Massacre and Arson, which were each rejected as my thesis. Even now, they inspire me to challenge so-called correct ways to work, think, and live. This may sound abstract, but when you see the exhibition you’ll recognize the continuity [between my past and present works]. The constant contrarian urge remains completely current. Look at “Oh My God,” “God.” Listen to Oh Diu, Diu—these Cantonese words are very much timely and reasonable exclamations. Hong Kongers should use them without shame or embarrassment. Diu is in the present tense; my June exhibition dedicated to Hong Kongers is in the present continuous.

Massacre, 1982

MKY: So are your works related to the current state of Hong Kong?

YJC: The works I create are related to the state of the whole world, of which Hong Kong is an extremely important part. I live in France and Germany, and I also live in Guangdong and China. I am an “overseas Chinese”—I am indeed a Chinese who is often overseas. I fly here and there. As I see it, diu [the state of being “fucked”] is not only in Hong Kong. Germany, France, Russia, China, the United States, and Japan—they’re all fucked. That’s right! That’s the attitude one needs now!

MKY: Your exhibition is titled “Good Morning Hong Kong.” Why?

YJC: Heung gong jo sun [“Good Morning Hong Kong”]. I like Hong Kong very much. Every time I fly there from Paris, I arrive in the morning. As soon as I get off the plane and say “good morning” to the city, I am breathing its ham sup hei [“salty-wet air”]. I love this ham sup [salty-wetness; Cantonese slang for lewdness], which nurtured me, this Cantonese guy, for 33 years.

MKY: You say that Hong Kongers are easily embarrassed. How do you explain this given the ham sup that you feel?

YJC: I was born in Foshan and matured in the swamps of Paris. Ham sup is good for me. I’ve missed the taste of the ocean for two decades. The moment I step off the plane, my mouth is filled with ocean air. “Good Morning Hong Kong” immediately brings to mind Good Morning Vietnam. During the Vietnam War, reporters from around the world showed what they could do in Hong Kong. Put more precisely, the Vietnam War was also won by art and the media. It’s the same today, isn’t it? Don’t forget this. If you forget, you become embarrassed easily. Respectfully I submit, Good Morning, Hong Kong.

MKY: This is not the first time you’ve participated in Le French May. The last time was 2001. What do you think has changed in 14 years?

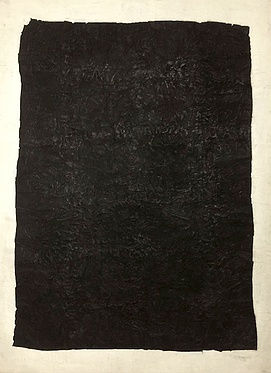

YJC: Oh, that’s a good memory. It was a large show curated by Mrs. Alice King at the Art Museum of the University of Hong Kong. At the time I was cultivating myself personally and artistically. I exhibited the Thousand Layers of Ink series, in which I effaced whiteness with black ink. I’d been putting ink on xuan paper, layer by layer, for over a decade, and it was about time I showed something. It was black enough (laughter). That was an uneventful time. I’d just left China. My environment and way of life had changed, and in my art I couldn’t keep rebelling against the Mainland art academies and artistic orthodoxies. Moreover, after the bullets were fired in Beijing, I became confused about whom and what I was. So I had to forge my own path, and I used that time to cultivate and elevate myself. After a near-death experience, one develops the ability to live unsullied in a polluted world. The opening line of the Daodejing—daoke, daofei, changdao ["the way permitted and the way denied [are both] constant ways"] as I read it—means that when you paint something so black that it cannot get any blacker, it begins to shine white. When you paint black to death, a new life emerges in it because of you. I released myself through art, which brought me true happiness. Now, years later, the world has changed. Faced with this cesspool of a world, how do we make it vital again? We throw some fresh seafood into it—the way Hong Kongers know best (laughter). So these two exhibitions are related like yin and yang and are mutually generative.

Thousand Layers of Ink, xuan paper, ink, gauze, 1990

MKY: So we may say “Good Morning” symbolizes a new beginning…

YJC: Exactly. You embark on a new journey. The sun rises again. You should invest your emotions, your heart into this new day. When the world is sick, you can’t be embarrassed anymore. If you shy away from things, you’ll be skinned, and even your marrows will be sucked dry. We should be angry like Spartan warriors. We should be fearless of death like Chen Sheng and Wu Guang. We should have the courage of those Cantonese in Sanyuanli who chopped foreign devils into pieces. When consciousness changes, so does the world. Once upon a time Hong Kong supported all of Guangdong. Guangdong changes China, and China changes the world. It’s all about consciousness! Salty and wet—what we have is this very salty and wet piece of land. I really want to become a ham sup gong [“salty-wet old man”] and become one of the half-man, half-sheep satyrs of Greek mythology. I may call my next exhibition in China “Ham Sup Gong—Satyr.”

MKY: (Laughter) Fine. As long as that’s what you want.

YJC: Good. It’s decided then.

MKY: But you have to understand that your works are very profound and subtle.

YJC: Not only that. They’re also very salty and wet, like satyrs. Maybe the Hong Kong government will deem the show “unsuitable for persons under 18.”

Mustard Seed Garden (humans and leopards), ink on silk, diptych screen, 2010-2014

MKY: Viewers will have to pay attention. They’ll have to look very closely to notice.

YJC: Inspectors are usually very careful. I’m worried that the Hong Kong government will censor itself at the beginning. That’d be embarrassing.

MKY: Hmm.

YJC: The exhibition will be an open and healthy environment, unless a viewer is sick. When you’re sick, nothing interests you.

MKY: Do you think of this exhibition as a retrospective? It includes works from 20 years ago, as well as current ones.

YJC: No. I don’t like retrospectives. Let’s think about that after I die. I’m grateful to Mrs. Alice King, who supported me over a decade ago when I needed help. A lady from a prominent family, she appreciated my dirty, “society-smearing” works, recommending them to the HKU Art Museum and even collecting them. I believe she had a vision. Out of respect for her, I decided to include some of the works in her collection, which will also allow the viewer to witness my development over the past 15 years.

This is Still Landscape Painting (Burg Utopia), exact copy of a watercolor by Hitler, paper, 1913-2013

Young Boy with Flowers, after a sketch by Hitler, bronze sculpture, 1913-2013

MKY: This exhibition is focused on the three media of gongbi [meticulous-brush] painting, ink calligraphy, and video. How do you think the venue will affect the reception to your works?

YJC: Do you mean the Central Library Exhibition Galleries?

MKY: No. I mean the public—Hong Kong collectors and critics.

YJC: I don’t think about the public. Take calligraphy as an example. For me, it’s a tool to elevate my character and quality of life, a method to cultivate my mind and taste. I like calligraphy. My calligraphy isn’t attractive, but I still like to ask myself why I do it this way. I try to find truth and beauty in my brushwork, even my mistakes. Calligraphy is my foundation, a tool for me to confront myself directly, my shadow. The Thousand Layers of Ink series is none other than my calligraphy. In these inky colors, one can still feel the character and energy of Qin- and Han-dynasty calligraphy. The Oh My God series, in which I copy and chant holy texts, index the exclamations of our era. Even my gongbi painting embodies the fluency, bone structure, and resonance of calligraphic lines. Calligraphy is one of the greatest cultural legacies of Chinese and even human civilization. In it I learn, work, and create. Here I’ve deliberately chosen a seemingly embarrassing point of entry, and chosen the ancient cultural instrument of the Chinese brush to express my contemporary consciousness, my love, and to voice my resistance.

MKY: I understand. But in Hong Kong, you’re faced with a highly developed system of Chinese ink painting. Here you’re easily categorized as a “contemporary ink painting,” although you have hardly anything in common with it. Do you think you’ve had any connection to contemporary ink?

YJC: That’s true. Hong Kong never experienced socialism and has maintained the traditions of classical Chinese culture. Experiments in contemporary ink have continually taken place here. Classical culture is indeed profound and populated by masters. After I greet it with a “good morning,” many avenues become wide open in front of me. And indeed, as a student I approached [the classical culture of] China through Japanese calligraphy. But my challenge today is not how to relate to contemporary ink, but how to escape from an embarrassing state in global contemporary art [globalization] through this embarrassing traditional method. I want to put together a group of works that’s equally embarrassing, so as to create the condition for resonances and chance encounters. It’s a good thing for everyone else to be suspicious of me. In the meanwhile all we need to do is to pray that each of us gets to shore safely. So when we meet, we’ll say to each other “hello” and “good bye.” I’m just passing through. It doesn’t even matter whether my works are related to contemporary art. I love being a passer-by. Contemporary ink hasn’t been my approach, but I’ve held a brush since I was a three-year-old boy with a shaky hand, and I’ve trembled with it ever since. Every person has his or her way of doing things. If we maintain an open attitude, art can bring us myriad joys.

Horse Painted in the Year of the Horse (at the artist's studio), ink and xuan paper, mounted on canvas, 2013

MKY: You’ll soon turn sixty. Do you still think of yourself as a young artist?

YJC: Aiya, what kind of question is this? Art is forever young. Would you believe that someone approaching sixty could create works like these? Art is ageless. A hundred years later, these works will still be young. Several centuries later, they’ll be seem even younger than now (laughter). This is what’s magical about art. Masterworks live for a long time and can hardly die. Look at Goya. For me, he’s much more contemporary than many artists working today. Look at the Tang-dynasty calligrapher Liu Gongquan’s Letter of Resignation to the emperor. It doesn’t seem to me to be millennium-old; it still impresses and inspires me tremendously. When you read Kang Youwei’s (my teacher’s teacher) thoughts on calligraphy, you find that he wasn’t just excavating tradition, but rather constructing an enormous cultural system to subvert the Manchu Qing regime. He wasn’t simply writing a history of calligraphy; he elevated calligraphy to the level of the collective consciousness of a people, setting the stage for a contest between north and south. Everywhere he spoke of change, change, and change, and in the end he really did cause a revolution! Consciousness is miraculous; once it changes, the times follow. Art needs this energy that’s at once material and immaterial. Today, people have forgotten about this. At the end of the Qing Dynasty, Han literati not only all read and understood Kang Youwei’s Guangyizhou shuangji but also participated wholeheartedly in revolutionary activities.

MKY: Are you a contemporary literatus?

YJC: I am a literatus. The designation of “contemporary” is unnecessary for the literati. Consider Ji Kang of the Southern Dynasties, whose free beliefs and expressions got him sentenced to death by the emperor. When asked what he wanted before his execution, he requested only a guqin with which to play Guanglingsan, a tune that has touched countless hearts over the millennia since.

MKY: What role do the literati play in contemporary society?

YJC: I believe that the literati are the elite driving force of a people. This force cannot be replaced by politicians or governmental functions.

MKY: What kind of force is this?

YJC: It’s like water: fluid, steady, flowing through rocks and forests, over hills and into oceans—a force without form, incessantly dying and returning to life, dissipating with water but unconstrained by death. The force is embodied by the pictographic meanings of the Chinese word for “civilization”—wen 文 and hua 化 [respectively, “pattern” and “change”].

MKY: What is the name of this force?

YJC: Wenhua 文化 is like mountains and like water. A mountain exists on its own; water flows by itself. Perhaps you can call it zizai 自在[existing on one’s own]—free and unconstraint. The Chinese characters shan 山 [mountain] and shui 水 [water] are both pictographic. The Chinese term for “politics,” zhengzhi 政治, is divinely inspired: zheng 政 is composed of zheng 正 [“upright,” “orthodox”] and wen 文 [“pattern”]. The latter zheng means balanced and centered. Wen encompasses reason and culture. Zhi 治 [“management”] is composed of shui 水 [“water”] and tai 台 [“platform”], indicating the construction of platforms and dams to guide the flow of water. With these characters, our ancestors left behind the lesson that politics means guiding people with culture. Divine words indeed! Today, politics have become a tool of robbers and thieves. But if you understand what these words mean, you know what culture is. (Translated by Alan Yeung.)