|

The latest exhibition by Ink Studio titled "Ink and the Body", running from September 21 to November 2, and curated by Britta Erickson and Nataline Colonnello, is the first of three from the "Ink and Phenomenology" series by the Beijing-based gallery. This group show brings together works by Chen Haiyan, Dai Guangyu, Huang Zhiyang, Li Jin, Qian Shaowu, Tao Aimin, Wang Dongling, Wang Peng, Yang Jiechang, Zhang Chunhong, Zhang Yu, and Zheng Chongbin. This first exhibition will be followed by "Ink and the Mind" and "Ink and the Environment," and according to Craig Yee, co-founder of the gallery, the three together (body, mind, environment/landscape) constitute "the world" in dialogue with phenomenology and Chinese philosophy.

Through a phenomenological approach, the body is presented as the manifestation of the self in interaction with the world through the mind. The exhibition relies on two principles taken from phenomenology that intersect with traditional Chinese philosophy: a) that "consciousness is embodied", and b) "self and world are co-defining and co-enacted." It is through these two phenomenological notions that the body takes a central role as it is represented by each artist in the exhibition. Lacking the kind of Cartesian mind/body dualism that dominated much of modern Western thought, major strands of Chinese philosophy are compatible with many of the core assumptions of phenomenology, which rejected the Cartesian view of selfhood. Thus the artworks in the show offer sites of intersection between phenomenology and Chinese philosophy with the body representing the self and the subject, and ink as the medium of expression.

In relation to this exhibition, one could think of phenomenology as "a methodology for a highly critical and rigorous observation of subjective experience." Given that the Cartesian mind/body dualism is rejected in phenomenological study and considering also that Chinese philosophy precedes phenomenology by centuries, we arrive at the conclusion that the processes considered as disembodied or transcending the body ("rational, analytical, conceptual, linguistic") can also be considered from the standpoint of "embodied neurology", embodied experience and embodied mind, as Yee suggests.

The first principle of embodied mind (and consciousness) leads to the idea that self and world are "co-defining and co-enacting." From the interactive dynamism between self and world, we can evaluate these two from the separation between internal and external realities, the subjective and objective, and inner (world) and outer (world). If one thinks of self as the product of both "nature" and "nurture," the world gives us our body and its genetic endowment through millions of years of evolutionary biology and the historic fact of our conception and birth while our knowledge and understanding of the world is constructed over a lifetime through our embodied experience of the world and our cognitive responses to it. The body thus becomes the point of these intersections between the self and the world, and mind and matter, a point of departure from which we build our experience as we define our existence and as it defines us. It is thus through the expression of the body through ink that the exhibition explores the relationship between self and the world.

Each of the artists in the "Ink and the Body" exhibition is engaging the body while employing ink as a medium of expression. Li Jin is painting the body in a self-satirizing and humorous manner using a traditional language of ink painting but with a contemporary subject matter. Zheng Chongbin is exploring how his experience of relating to others enabled him to producie an art that is based on altered understandings and perceptions that emerge from his process of empathizing with the disabled body. Chen Haiyan is painting the body as a product of subjective experience emerging from the subconscious and from dreams. Huang Zhiyang is introducing brushwork typically used to paint landscapes in a series of texture strokes that represent units of qi to revisualize the human body in its relation to reproduction and birth. Yang Jiechang is making use of Socialist Realism to confront his viewers with a social reality of violence and trauma from the Cultural Revolution and using ideographic lines to represent the body from a Confucian adage.

Zhang Yu is reconceptualizing the idea of gesture by replacing brushwork with fingerprinting to reflect the bodily meditative repetition that leads to an altered state of mind. Dai Guangyu is engaging with the body as a canvas or paper that absorbs and reflects Western and Eastern practices and knowledge. Wang Peng is recording the gestures of the body using ink to capture gesture and form by going against traditional practices. Tao Aimin is excavating an unwritten history of the daily experience of women as the human body engages with manual labor. Zhang Chunhong is depicting a part of her body (hair) as natural phenomena (waves) such that the hair as meronym represents her individuality. Qian Shaowu is intersecting and reconciling the rhythmic musical quality of his brushwork with the need to depict the female body in a realistic manner. Wang Dongling is layering text, image and calligraphy to match the calligraphic gesture and movement with the posture and movement of the human body.

Li JinLi Jin works in a very traditional language of ink painting but with a contemporary subject matter. Adopting a self-satirizing and humorous tone, he depicts himself and his life from the outside using consummate brushwork and vibrant, translucent colors. These two portraits are the first in a new series of works, using rough and informal brushwork and ink monochrome, Li Jin depicts himself and his partner from the inside looking out. In these two works titled Ink Hermit 泼墨山人(2014) and Ink Fairy 泼墨仙女 (2014) Li Jin is doing figure painting, in particular portraiture. Portraiture becomes popular during the 6th century at the time of Xie He, who apart from being a theorist (and developer of the "Six principles of Chinese painting") was also a portrait artist. Li Jin is interested in capturing the essence, character, spirit and personality of the portrayed through highly expressive calligraphic brushwork known as da xie yi. According to Yee, the whole idea of the artist, brush movement, bodily movement being directly tied to and a direct reflection of the mind again uses the first phenomenological principle of embodied mind such that the physical mark is in fact a mark of the mind.

Zheng ChongbinZheng Chongbin's Another State of Man series from 1987-88 is from his early figurative works that reflect a personal aspect of his biography. The series was produced from Zheng's interaction with his disabled sister who he grew up with and whose disability changed the way he considered gesture, movement and anything related to the human body. Empathizing with the physically disabled body allowed Zheng to relate to his sister from an altered standpoint, getting to know her movements and gestures and adapting to a varied understanding of posture and bodily motion. Living with his sister influenced his understanding of what it means to be in the world and altered the way he sought to relate to others through a shared experience of this being in the world.

His views on how we experience the world through others came to defamiliarize his understanding of the human body and movement with his sister being his primary teacher. He would watch her, amazed by the way she would move, sometimes using props and tools to move around in order to augment and extend the body. This really helped him defamiliarize the whole idea of movement, and de-habituate his own preconceived notions of motion. Even though a classically trained painter, he became interested in this shift in perception and understanding, which ultimately drove him to produce these works, presented originally for the Shanghai Art Museum in 1988.

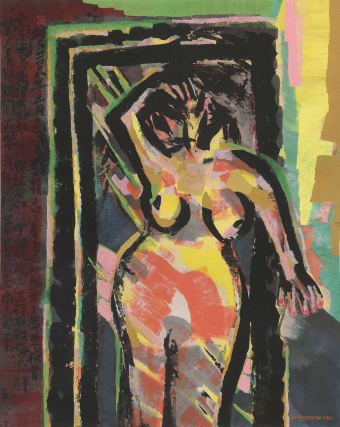

Chen HaiyanChen Haiyan is recognized for her artworks that she paints from recording her dreams in dairies that she keeps by her bedside. For this exhibition she presents two works, Look into the Mirror (2014) and The Cloth Shelter (2014). According to Yee, when we approach her work, Zhuangzi's tale about the dream and the butterfly comes to mind. As the story goes, Zhuangzi dreams that he is a butterfly and when he awakes he does not remember whether he is awake or within the dream of the butterfly. Similarly, Chen Haiyan from a phenomenological perspective is reconfiguring the principle of self and world being co-defining given that the world in her case emerges from her subjective experience, from her subconscious, as her dream-world, from within.

Both Zhuangzi and Chen Haiyan engage with the dream in such a way that through it they are able to experience the Otherness of their world, as Others and as themselves at the same time. From within, Chen Haiyan is able to engage with her subjective experience as an Other, as someone who lives within her dreams and is brought into her world through the artwork. The artwork thus becomes the extension of the dream into her reality and into her wakefulness, as if she were awakening into her dream, a dream that can be accessed not by falling asleep, but by being awake. The artwork establishes the continuity between the dream-world and the world of her wakefulness.

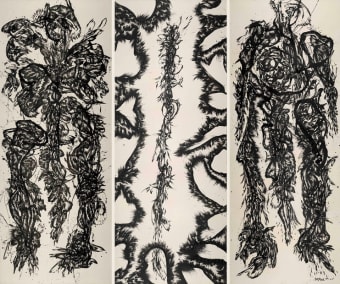

Huang ZhiyangFor this exhibition Huang Zhiyang presents Zoon-Beijing Bio No. 1001 (2010), a triptych in which he depicts two male figures on the right and left sides and the birth canal in the center. According to Yee, from a Chinese perspective, the birth canal is also a metaphor for either the portal or gateway that links two worlds, of existence and non-existence, or chaos and form, or being and non-being. The transition from non-being to being is conceived in the Daoist perspective as the gate. These works of Zhiyang come from neo-Confucianism, or the intersection between Confucianism and Daoism. As Yee suggests, these works can be placed in a Song frame given that the brush technique employed is the cun.

The cun is a texture stroke that is used repeatedly as a way of defining a surface and is used mainly as a method of painting landscapes, which are made of thousands of these small texture strokes meant to describe form. Huang Zhiyang appropriates this method to paint figures with each stroke approached from a gestural perspective as "an individual gestural unit of energy". According to Yee, the stroke itself "becomes a metonym" for a qi or a single unit of energy, which in the Chinese tradition is the universal substance of the world. Huang thus becomes a mediator and keen observer of his own body and these paintings are, in a sense, a map of these first-person introspective explorations of the human energy.

Yang JiechangYang Jiechang presents his graduation project from 1982 titled Massacre, from the period right after the Cultural Revolution. In this work he is reclaiming Socialist Realism, originally brought into China through Russia. Socialist Realism was used in China in the early 20th century to erase people's social, political, moral awareness by confronting them with their social reality. It was then employed for political purposes to mobilize people ideologically, but then after the political revolution was a success, it was no longer about mobilizing people but about indoctrinating people and so it became propagandistic. According to Yee, in Massacre, he is reclaiming its original role and painting the tragedy and massacres of the Cultural Revolution in order to wake people up to the reality of the horror that they experienced. This was thus not acceptable, and as a result it was rejected by the graduation committee at Yang's school, and censored, so he had to present another work in order to graduate.

Yang Jiechang's 1987 work titled Three Men Walking, is based on altogether different, indigenously Chinese aesthetic and semiotic principles. Three parallel yet curving lines, painted in a calligraphic manner to the scale of a human figure, stand within field of raw paper. If this were drawn as a calligraphic graph, one's first instinct would be to look up its gloss in a dictionary and then perhaps memorize its definition through some clever visual mnemonic. Yang reverses this experience. Standing in front of his life-size graph, one senses the presence of three figures standing. In the center of the central stroke, a round dot pulses at about chest height distinguishing one line from the rest. The title of the work, Three Men Walking refers to a line from the Analects of Confucius: "Three people walking, [one of them] must be my teacher." Without recourse to explicit semiosis, Yang's meaning flows intuitively and spontaneously from one's direct, embodied experience.

Zhang YuZhang Yu is a traditional painter who became interested in thinking conceptually about what gesture means in a painting. In this work titled Fingerprints (2006), he abandons the brush and instead creates a painting using only his fingerprints, unlike classical finger painters such as Gao Qipei (1660-1734), who used their fingers, nails, and palms largely in service of representation. The painting is made through a very simple process of repeated physical gestures creating a visual field of varying densities of pigment. The darkest areas in the painting are the overlap between several fingermarks; the lightest, untouched raw paper. According to Yee, the work explores the relationship between gesture and mind and specifically painting as a physically repetitive process that becomes a mental meditative process.

In that sense, the work reminds of Buddhism, of which there are practices that involve reaching a meditative state through a series of repetitive breaths to build focus. Through these series of controlled finger touches, Zhang Yu is creating a meditative practice through which the physical gesture is able to alter mental experience. Embodied consciousness is thereby shaped by the body. The brush gesture is a primary means of expressing a state of mind in Chinese painting, but Zhang Yu is taking the brush away and using the physical body (finger prints) in a repetitive process to induce a state of meditative stillness. The resulting work can be seen as a visual metaphor for the applied phenomenology developed and practiced in Buddhism.

Dai GuangyuIn the 1999 performance Absorbing, Being Absorbed, Dai Guangyu dresses in white and is bathed in ink from tubes placed directly above him while he imbibes a substance which appears to be ink from a baby bottle. In many of his performances Dai Guangyu is dressed in white, transforming his body into a sheet of paper, whose function is to absorb, as he also does by drinking. There are two forms of absorption: the baby bottle filled with coffee-a symbolic carrier of Western culture-as the conscious intentional absorption of western influences, and the other with actual ink that is dripping from his environment and consuming his whole body, serving as a metaphor for Chinese civilization. One is intentional and actively ingested, while the other is unintentional and environmental. He is rebelling in the way the Chinese artists have interacted with the medium of ink. According to Chinese tradition, ink is supposed to be the means by which one records one's gestures and in doing so expresses one's mind. The performance reveals the intersection of Western ideas about performance art with Eastern concepts.

Wang PengWang Peng's performance titled 84 Performance was the first nude art performance in China performed at the Central Academy of Fine Art. According to Yee, the performance is an amazing embodiment of the post-Cultural Revolution era when Chinese society was opening up and anything seemed possible. "The feeling of potential mixed in with the frustration resulting from the constraints of society led to the tension which produced the energy to make this work", Yee notes. Ink was readily available and so Wang Peng used it to make prints even though he is not an ink artist and is mainly a conceptual and installation artist. By using ink in his particular way, Wang Peng not only breaks with tradition, but wants to change that tradition by adopting ink in such a radical way that is affront to traditional propriety. In that sense, as Yee suggests, this move is completely anti-Confucian.

Tao AiminIn The Secret Language of Women (2008) Tao Aimin presents an installation of washboards used by Chinese women and a series of ink rubbings of the washboards collected in a series of books. In this work, Tao Aimin employs Nüshu, a form of writing from Hunan province developed by women to transcribe their local dialect syllabically. In this work and another series titled Woman's Journal (2009) Tao Aimin is able to present the reality of Chinese women that is otherwise not recorded nor preserved. Through these two series of works, she presents the everyday reality and experience of women. According to Yee, the rubbings of the washboards is based on a technique developed to record surfaces, images and written inscriptions on stone epitaphs from the Han and Wei period, and on bronze vessels from the warring states and the Zhou period. The works make use of physical artifacts to reconstruct Chinese history, and in this particular case to excavate and reconstruct the history and reality of women, as Yee notes.

Zhang ChunhongZhang Chunhong presents her charcoal on paper work titled Waves (2013). She has a twin sister and both have long flowing hair. As such, she represents her hair as an index of herself. In this work, she is using hair to depict waves, to present a part of the body as a natural phenomenon. The hair in the work is used to represent her identity transposed into a natural form; waves. The hair represented as waves thus becomes a meronym that represents the individual. As such, the hair as waves is presented as the mark of the individual transformed into the mark of nature.

Qian ShaowuQian Shaowu is one of china's most famous sculptors of the modern period. He is Russian-trained and his sculptures are based on the idea of Social Realism. According to Yee, in this series of works titled Figure Line Drawing (2014) he is reconciling the modeling of realistic form with the gestural brush. There is an inherent contradiction in that the gestural brush wants to move by abstract dictates. We think of these works in terms of gestural aesthetics and there is a musicality to the brush based on a different set of criteria; the need for the line to depict is intertwined with the musical motion of the brush. The tension between creating something realistic as opposed to something musical, is the tension found in these works. Choosing the rounded form of the female nude, Qian is able to accomplish both the rhythmic musical quality of the brushwork and the need to depict the figure in a realistic manner; he is able to reconcile both.

Wang DonglingIn the 80s and 90s, Wang Dongling spent some years in the US, where he saw a New York Times article on the American dancer and choreographer Martha Graham. Graham's physical posture in motion inspired Wang to respond in kind and, picking up his calligraphic brush, he dashed off rhythmic ink strokes directly onto the dancer's image that echoed the her form and movement. This resonance of movement between world, mind and body, what the Chinese call qiyun is the central desiderata for brush and ink painting. Since then Wang has embarked on a whole series of works of calligraphy in response to the human body, and began using art photography in books, magazines and newspapers. In these series of works, he combines calligraphy, with the form of the character related to the human form, and also relating the movement of the brush to the movement of the human form. If the brush represents gestural language, he is directly and explicitly exposing that relationship to the body, with the form complementing the movement of the body. The various texts he uses are usually poems that he selected as a form of supplementary linguistic commentary to produce these multi-layered works.

References: Interview with Craig Yee, co-founder of Ink Studio (Beijing) on September 23, 2014. |

Ink and the Body: A Phenomenological Approach

Amjad Majid