|

Yang Jiechang's exhibition "This is Still Landscape Painting" displays a very heterogeneous body of works. The artist confronts the public with early twentieth century Western flower and landscape painting, with a set of works that echo the Western idylls using a technique and style reminiscent of Northern Song Dynasty court painting; calligraphies; and, finally, works belonging to one of Yang's recent series entitled Mustard Seed Garden. Even though heterogeneous, the ensemble is not incoherent; on the contrary, the association of different subjects and styles creates a strong, yet disturbing dialogue.

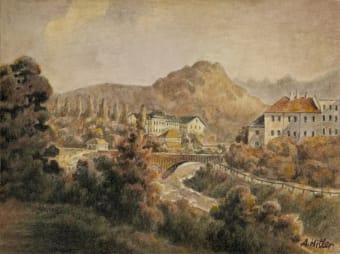

The Western flower and landscape paintings are actually authentic copies of paintings done by Adolf Hitler between 1904 and 1920. These works are juxtaposed with copies of the same paintings in the style developed by Northern Song Dynasty emperor Huizong (r. A.D. 1100-. 1125) and his painting academy. Both sets of copies find an answer in the Mustard Seed Garden series, in particular in the large 8-panel landscape subtitled Tale of the 11th Day.

One focus of the exhibition seems to be the practice of copying. But why copy mediocre landscape and flower paintings by a most reviled figure in modern history in two different fashions, first authentically and then again in the style developed by a Chinese emperor? What does Yang Jiechang hope to experience through the process of copying, and what is for him the connection between these two historical figures?

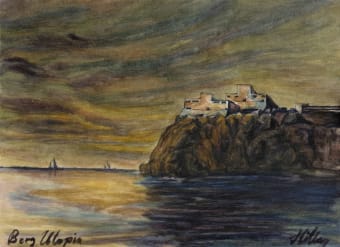

To answer these questions, let us first have a look at two paintings, one present in the exhibition, an authentic copy of a Hitler watercolor, entitled Burg Utopia (Castle Utopia), the other a seminal Northern Song Dynasty work attributed to the Huizong emperor, with the title Auspicious Cranes.

Castle UtopiaBurg Utopia—Castle Utopia—is a small watercolor showing a kind of modern fortress on a cliff above the sea at dawn. Castle and landscape are depicted in a most general, even stereotypical, manner. Just a few details locate the fortress in a modern or future time rather than in the past, a time yet to dawn as also indicated by the work's title. The painter nevertheless pays particular attention to the rendering of the atmosphere at dawn. The strange castle with its rigid and cold functionality is bathed in a warm golden light, which generates an awkward contrast. This clumsiness is enhanced by the sentimental tone of the depiction. The actual choice of the subject seems awkward, too. What does this castle that resembles some kind of gloomy penitentiary rather than a fortress represent? What kind of golden future could this sinister sign bring about? The question is not an innocent one and history has the terrifying answer to it. Let us have a closer look at the painting.

Hitler painted this watercolor in 1909 during his time in Vienna, where he associated with members of the Ordo Novi Templi (an occult group promoting the superiority of the so-called Aryan race and aesthetics, and employing the swastika as symbol). One can suppose that Burg Utopia is linked to the influence of the occult circles and the Ariosophic movement. It might even be inspired by Burg Werfenstein, refuge of the Ordo Novi Templi since 1907. What we can say for certain is that this painting different from the other landscapes painted by him during this time, which are stereotypical Southern German and Austrian postcard idylls or scenes from World War I. By contrast, it depicts an imaginary place and stands for some kind of utopian ideal.

Auspicious CranesAuspicious Cranes (1112 A.D.) is a painting in the traditional gongbi or meticulous color technique. The work that is attributed to the Northern Song emperor Huizong shows, as suggested in the title, a flock of cranes circling above the palace roofs. The emperor recorded the unusual occurrence, which was considered a good omen, through this particular painting as well as through a poem and colophon inscribed next to the painting. Huizong, who was a Daoist, paid particular attention to such auspicious signs and had them spotted and recorded. As we learn from his inscription this particular omen occurred during the Lantern Festival of the year 1112 A.D. during the New Year's celebration and above the Duanmen palace gate, from where the emperor showed himself to his subjects. The appearance of the good omen was interpreted as Heaven's approval to the actual reign.

As scholar Maggie Bickford shows, the painting can be considered "the most impressively impersonal in pictorial image." And she continues, "Even among Huizong's highly stylized images, Cranes of Good Omen [i.e., Auspicious Cranes] is distinguished by its opaque beauty and compelling pattern."[1] The white cranes that stand out against a dark blue sky, even though rendered with many details, are not depicted in a naturalistic manner but indeed as a kind of pattern. They appear rather like some kind of universal schemata or, as Bickford puts it, "archetypes that constitute an authoritative imperial image"; yes, "the image seems to appear in its own accord—like an omen."[2]

Yet, as Huizong's poem suggests, the cranes were not merely understood as a sign of heavenly approval but also considered emissaries of the Immortals' eternal celestial court transmitting their blessings to the worldly emperor. As Bickford further shows, Huizong's painting associates the archetypal and timeless aspect of the image with "the particular and the circumstantial."[3] The impersonal aspect and the opacity of the image finally aim at creating a perfect authoritative image that cannot be doubted. Auspicious Cranes can therefore be understood as a programmatic painting, yes, as a propaganda painting.

It is interesting to note at this point the particular position of the Chinese emperor as Son of Heaven, as a link and pivot between the eternal and the timely, the celestial and the earthly. The belief in the existence of a metaphysical system operating behind and having an immediate effect upon the earthly one here transcribes itself directly into politics through ceremony and culture. Music in particular was an instrument to link and generate harmony between the two spheres. The proper music played at a righteous emperor's court was believed to catalyze the occurrence of auspicious omens, such as white cranes.[4]

What was considered a fundamental belief and prerequisite of a good reign for a Chinese emperor would seem madness if chosen as a conviction and foundation of government by a Western politician. Nevertheless, I think it is exactly this aspect—the belief in some kind of supernatural system operating behind the earthly one—that links Hitler's clumsy idylls with the sophisticated paintings of emperor Huizong. The dark, impenetrable aspect of the paintings is expressed differently by both historical figures: while Huizong tries to reach a most impersonal expression, Hitler by contrast searches for a most sentimental one. For Huizong the image is a manifestation of spiritual principles conditioning reality. The semantic difference between symbolic existence and real existence is eliminated. The image appears on its own accord and, as a kind of omen, has a direct impact on reality. For Hitler, on the other hand, the image is a mere cliché, not even of reality but of a stiff idyll or of some murky utopia. The viewer feels the painter's limitation not only to represent but also to apprehend reality.

Mustard Seed GardenThis intriguing aspect, as well as the opacity of the images created by both historical figures, might have been one reason for Yang Jiechang's interest in the subject. The contemporary artist was attracted by the dark and impenetrable elements in the paintings. Initially, however, it was another aspect that triggered the artist's curiosity. Both Hitler and Huizong are reviled historical figures and both shared a strong interest in the arts. Hitler, as we know, even though an ardent student of painting, could not realize his project of becoming an artist, and sarcastic voices trust that the history of the twentieth century would have been less tragic and millions of lives could have been spared if he had pursued an artistic instead of a political career. Emperor Huizong was a talented painter and calligrapher, and as a great patron of the arts he set the aesthetic standards for Chinese culture, still considered valid today. However, Chinese historians generally consider his love for the arts and his focus on culture over other state matters as one of the reasons why the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127) ended in debacle.

Yang Jiechang approaches both personages from the angle of art and culture through the method of copying. Doing so he eschews historical judgment as a sole and first approach to these historically problematic figures. In the tradition of Chinese painting the copying of model works is the fundamental method to acquire the required technique and style, and Yang as former art student and teacher at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts is only too familiar with this kind of method. As mentioned above, he copies in two different fashions: first, authentically and then in the style of Song emperor Huizong.

One of Song Huizong's bird and flower paintings was actually the first painting Yang ever copied at the beginning of his artistic career. But this time the models the artist copies are not the masterworks of an emperor who is also a famous painter, but instead the efforts of an insignificant art student who finally became a dictator representing the archetype of fascism. Yang Jiechang's choice of this kind of model is an extreme and a courageous one. It seems that there are no positive elements the artist could learn from copying this kind of painting. The field he probes into is overly charged with negative sentiments, moral convictions and political positions, and raises questions that still cannot be discussed impartially today.

Confronted with this kind of dilemma Yang Jiechang refers to the late Czech artist Miroslav Tichy, who made fascinating photos with self-made cameras and lenses. Tichy's conviction was: "If you want to be famous in the world, you have to do something worse than anybody else in the entire world. Something beautiful and perfect is of no interest to anyone."[5] Yet, for Yang, copying the paintings of a problematic historical figure in the style of a controversial historical figure was not a strategic but rather a fundamental choice. He states: "If you choose such an extreme position, then you choose the freedom of art."[6]

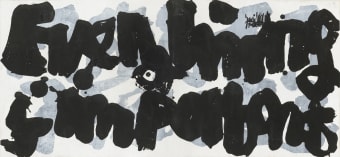

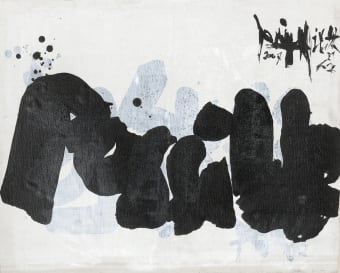

This attitude prevails throughout Yang Jiechang's oeuvre. His calligraphies, for example, are written upside down, and the artist consciously uses dripping and strokes that according to traditional Chinese aesthetic standards are considered inelegant and false. The same is true for his Hundred Layers of Ink series (1988 - 1999). Here Yang superimposes layer upon layer of ink to produce monochrome black paintings. By doing so he reduces the medium of Chinese ink painting to its basic elements: water, ink, paper, and the process of painting. The result is a black meditative space rather than a surface, a space that pushes to extremes traditional Chinese ideas, such as the Daoist aesthetic concept of the unhewn, of change and relativity—the black shiny ink captures the light and thus may appear white. Further, as any kind of representation or traces of the artist's personality are absent in this kind of work, Hundred Layers of Ink also evokes the Chan Buddhist notion of self-sublimation.

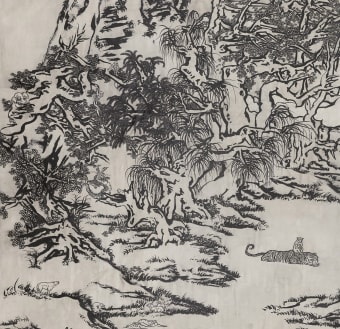

Mustard Seed Garden is another example of such extreme procedures. The artist is referencing the early Qing painting manual with the same name, and his painting explicitly relies on models stemming from the canon of traditional Chinese landscape painting. Within this classical scenario Yang stages the interaction of animals of different species, as well as that of human beings with animals. The depiction of dissimilar modes of communication by the animal couples, ranging from curious discovery to playful contact and joyful mating, is executed in a most meticulous and traditional manner, but the represented subject is all but orthodox.

This extreme juxtaposition opens up a space of astonishment and bewilderment allowing new perspectives. Yang's classical Chinese panorama suggests a kind of universal, eternal landscape, in which boundaries, difference and prejudice seem to be forgotten. All interplay seems equal, compassion and love. His image of a land where impartial communication and action is possible reminds me of a globalized world, yet one based on equality, on mutual respect and compassion. Thus Mustard Seed Garden—Tale of the 11th Day would be the allegory of such a utopia, of this kind of age-old dream. Yet equality, respect, compassion, love, and hence harmony, are instable relations. Once the balance between the big and the small, the strong and the weak, the one on top and the one below is jeopardized, the result is disparity, contempt, indifference, hate, and aggression. Yang reminds us that even though all beings are interconnected in an essential unity of existence, harmony is still based on power play.

As we see, Yang Jiechang dares to touch on taboos. The process of copying, as well as the use of classical models and pattern, seem to be an adequate method for dealing with the controversial subject. The apparently merely technical approach allows a quasi-neutral position. In a way similar to that of E.H. Gombrich who used a white grid covering a reproduction of a Constable painting as an analytical tool "to see the painting for what it is," Yang Jiechang uses copying as an analytical method to look at his models and their authors for what they are.[7] By copying the works of a most reviled historical figure in the style of another problematic personality Yang raises the question of the innocence of his model, of the innocence of the image itself, and, further, of the innocence of the viewer, whose judgment is always bound to relativity and change.

[1] Bickford, Maggie, " Huizong's Paintings. Art and the Art of Emperorship" in: Patricia Buckly Ebrey/ Maggie Bickford (eds.), Emperor Huizong and Late Northern Song China. The Politics of Culture and the Culture of Politics, Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Mass.)/ London, 2006: pp. 459-464. [2] Bickford: p. 461. [3] Bickford: p. 463. [4] Ibidem [5] Quote from: Miroslav Tichy, Tarzan Retired, film by Roman Buxbaum, 2006. [6] Conversation with Yang Jiechang, November 2014. [7] Gombrich, Ernst H., Art and Illusion, A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation, The A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts 1956, Bollingen Foundation Series XXXV. 5, 2nd edition, New York: Pantheon Books, 1961: p. 305.

|

Reinterpreting Omens: Castle Utopia and Cranes of Good Omen

Martina Köppel-Yang