|

THE GREAT SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY Chinese painter Shitao 石涛 (1642-c. 1707) stated that the artist should "establish spirit in the sea of ink" 在于墨海中。立定精神.1 While it has always been a challenge for painters to establish an independent spirit through ink, or thereby to express the spirit of the world in which we dwell, the difficulty has been compounded. Past masters have left a vast and formidable sea of ink, one in which it has been problematic for late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century painters to find a way, particularly in light of the encounter with Western art. Zheng Chongbin's innovative abstract ink works demonstrate that the greater the challenge, the more profound and revelatory the solution.

The major art movement of the twentieth century, abstraction, developed from the converging interests of artists of diverse cultural backgrounds. Although the Russian Suprematist Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935), the French Nouveau Réaliste Yves Klein (1928-1962), the American neo-Dada artist Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008), and the numerous other artists who contributed to the development of abstraction had different impetuses and goals, a popular narrative of art history often gives the impression that a single thread spun out of Cubism, through Surrealism, and on to abstraction, arriving by mid-century at Abstract Expressionism and minimalist field painting. Zheng Chongbin's late twentieth and early twenty-first century abstractions evince an awareness of the genre's many threads, while simultaneously spinning a new one. His oeuvre thus adds to the exchange between Euro-American abstraction and East Asian art and philosophy, an exchange that traveled East to West through such figures as the composer John Cage (American, 1912-1992) and the painter Mark Tobey (American, 1890-1976), and from West to East, contributing to the avant-garde Fifth Moon Group in Taiwan and Gutai in Japan, to name just a few major figures and groups taking part in this cross-fertilization process. The richness of these exchanges has been explored in such exhibitions and publications as Alexandra Munroe's The Third Mind: American Artists Con-template Asia, 1860-1989 (Guggenheim Museum, 2009),2 Michael Sullivan's The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art from the Sixteenth Century to the Present Day (1973),3 and the collection of essays Discrepant Abstraction (2006).4

Coming out of a strong background in traditional Chinese ink painting, Zheng Chongbin brings two important aspects from that tradition to bear on abstraction: an extreme art-historical awareness and a belief in the centrality of art language. For him the former extends beyond the traditional Chinese painter's consciousness of his native antecedents to embrace both Chinese and Western art history, from early paintings on neolithic Chinese pottery through the classic periods of both East and West, and up to a fascination with the light sculptures of Dan Flavin (American, 1933-1996) and the conceptual projects of Lawrence Weiner (American, born 1942).

Zheng Chongbin's oeuvre has evolved as an unplanned, but powerful, response to the historical Chinese canons of painting.5 In deconstructing the traditional precepts of ink painting, he has employed diverse contemporary art concepts to forge a new model of ink painting. The result (I paraphrase Yee) is the deconstruction of objective form to embrace abstraction, and the displacement of mentally constructed space by viscerally perceived space.

Zheng Chongbin's drive to arrive at a creative situation where the media and artist cooperate to produce works implies the overarching importance of art language, siting him in agreement with Shitao as well as with the American mid-century modernist Jackson Pollock (1912-1956). Pollock once said, "Something in me knows where I'm going, and--well, painting is a state of being... Painting is self-discovery. Every good artist paints what he is."6 When artists arrive at such a point of understanding, there is the sense that the art is following a natural path of development, natural for the artist and for the medium. The art is no longer primarily a vector for an idea expressed initially in words; it is a plastic idea expressed in plastic form without verbal intervention. Art language becomes central to creation and to viewing, and artists in diverse places and times have instinctively understood this. Contemporary artist Zheng Chongbin, seventeenth-century master Shitao, and twentieth-century painter Pollock all arrived at such an understanding. Born into a China with a convoluted art history, Zheng has redirected ink painting back toward the natural development of a personal art language that feels intrinsic to the material.

CHINESE HISTORICAL BACKDROPThe past century has been a time of turmoil for Chinese ink painting. Prior to the twentieth century, landscape was the elite genre. The landscape itself was not, however, the artist's subject. Mimesis was scorned to such an extent that, as early as the eleventh century, the scholar Su Shi 苏轼 (1037-1101) wrote, "If anyone discusses painting in terms of formal likeness, his understanding is nearly that of a child" 论画以形似, 见与儿童邻.7 Instead of seeking likeness, the artist's concern was to use the landscape form as a vehicle through which to express a sense of self in communication with the Dao 道,8 and to engage in a dialogue with artists of past, present, and future about the language of brush and ink.

This interpretation of landscape, instigated in the Song Dynasty (960-1279) and fully implemented in the Yuan (1271-1368), had continuously evolved over the course of centuries, arriving at its zenith as an immensely sophisticated means of artistic expression. The "mind" landscape9 persisted as the dominant genre until it received a shock in the nineteenth century when confronted by the imported Western imperative of realism. During the Maoist era, this centuries-lived understanding of art language's centrality to art was decimated.

In his 1942 "Talks at Yanan on Literature and Art," Mao Zedong stated that art was to be created for the workers, peasants, and soldiers: it was to be based on an understanding of the struggles the people faced, and executed in a manner they could comprehend. Furthermore, its goal was to support ongoing revolution. Under these precepts, traditional ink landscape painting was proscribed as bourgeois liberal, and Socialist Realist figure painting-imported from the Soviet Union--in oil or acrylic on canvas, rose to be the dominant genre. This had a devastating effect on Chinese art. Propagandistic figure painting is readily comprehensible, as Mao required: it is an exaggerated mode of storytelling. The figure is key, and beyond such obvious devices as bathing heroic characters in light, siting them at compositional center, and exaggerating gestures and expressions, the content functions on the surface: what you see is what you get. Thus, in mid-twentieth-century Chinese art, the landscape as a kind of non-subject, ink, and art's deep philosophical underpinnings all fell by the wayside, upheld sporadically and sometimes secretively by an older generation, but rarely passed on. Born in 1961, Zheng Chongbin was a teenager when the oppressive period known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution came to a close in 1976. Growing up during what was a cultural low point for China, he was fortunate to have had the opportunity for private study with accomplished masters.

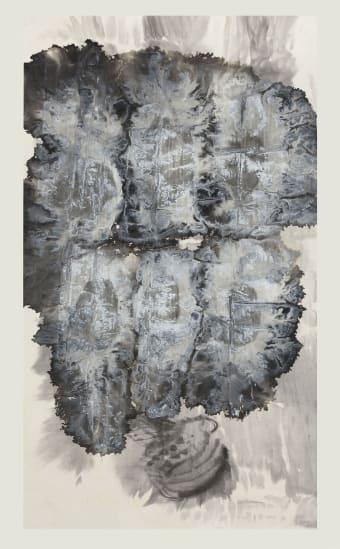

ZHENG CHONGBIN PAINTS A PAINTING10The walls of Zheng Chongbin's studio are hung with his most recent paintings, some complete and mounted on a paper backing ready for framing, and some still waiting for the finishing touch or even a major redo (fig. 1). Everything is black, white, and gray. Plastic sheeting covers the floor: this is the surface on which Zheng paints. One end of the studio is filled with materials: brushes, boxes of bottled ink neatly stacked on a small shelved cart, a couple stools, two ladders, and white plastic buckets of water, dilute acrylic, and ink. The artist chooses two sheets of xuan 宣 paper and spreads them next to one another on the floor, parallel and abutting, but missing exact alignment by about seven inches. The dislocation will catalyze the creation of a sense of a shift or twist in three-dimensional space.

Since the Tang Dynasty, xuan paper has been produced in Anhui province, the home of the Four Treasures of the Scholar's Studio: brush, ink, paper, and ink stone (文房四宝:笔, 墨, 纸, 砚 wenfang sibao: bi, mo, zhi, yan)--the latter for preparing the ink. Although Zheng Chongbin long ago purchased paper produced in the 1970s, it is stored away: he is saving it for his old age, as xuan paper improves with time, achieving a rich quality described as akin to fatty jade. The paper Zheng is using now is a kind called jingpi xuan 净皮宣 (pure skin / bark paper), produced with a high proportion of bark from the wingceltis tree. It is soft, malleable, and highly absorbent. Less absorbent xuan paper is available, but it is not suited to his purpose.

Kneeling, the artist smooths the paper on the floor, then rises to stir the contents of a bucket of diluted white acrylic paint. He pours bottles of ink into another bucket. Chinese ink, a product of soot with various additives, is ancient and elemental. In the past it was available only in stick form, the carbon bound with animal glue, but now is prepared conveniently bottled. Zheng Chongbin uses a good-quality bottled ink, and occasionally special lacquer ink (漆墨 qimo), which has a more reflective and intense black quality.

With paper, ink, and acrylic prepared, Zheng turns on the CD player. He says the music is a backdrop-he is not really listening as he picks up a brush and approaches the paper. The brush is a paibi 排笔 (row of brushes)--not a regular painting or calligraphy brush but a flat-handled wide brush commonly used in mounting paintings or in processes that require an even application of a liquid. He originally took up the paibi in 1985 as a means of breaking his habituated way of painting. He had studied traditional Chinese ink painting first with the masters Mu Yilin 穆益林 (b. 1944) and Chen Jialing 陈家冷 (b. 1937),11 and then at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts in Hangzhou (now the China Academy of Art): inevitably, he had learned to wield the maobi 毛笔 (hair / fur brush), the traditional brush perfected over the course of millennia, perfectly designed to hold and to evenly release a well of ink stored in the middle of the brush end. The maobi is the tool that ties ink to xuan paper in a harmony of materials perfected centuries ago. The maobi's handle is round, and artists are taught to hold the brush in such a way that, through minute adjustments of the fingers, the brushstroke can be directed in myriad ways. Decades of training result in a mastery of the brush retained as motor memory: in wielding the brush no conscious action is required. This is what Zheng Chongbin sought to break through by using the paibi, describing the result in a 2006 interview: "Ironically, the way I use the paibi is the same way I use the traditional brush, the same movements-in other words, although I imitated the traditional brushwork, I found it was interesting because the change in brush changed my behavior, the movements. The mix is interesting."12 Six years later, working continuously with the paibi has changed his behavior even more, but he remains in consummate control of the brush.

Having prepared all, Zheng Chongbin considers the paper, and then he is in the zone, ready to paint. The initial steps take place with no interruption. Dipping the paibi in ink, he paints on the first wide brushstroke, with about ten more following immediately: the structure of one of the pieces of xuan is established, a black rectangle angled so that its corner impinges on the second sheet of paper. He has used a wooden stick laid on the paper a few times as an aid to creating straight lines. The ink washes are heavy enough that they bleed into the absorbent paper, continuing to spread outward as Zheng works on the second piece of paper. He rapidly brushes dilute white acrylic onto the second sheet of xuan to form a large rectangle, then dips a brush in water, swipes it across a palette to pick up some ink-tinged acrylic, and adds wet gray along the edges. Returning to the first sheet, he pours a dollop of acrylic on top of the ink, then spreads it with a squeegee. By this point, the wet ink has caused the paper to wrinkle extensively, creating complex ridges that capture the paint from the squeegee. Zheng next turns to the second sheet and adds dilute ink on top of the acrylic, the ink pooling in the wrinkles' hollows (fig. 2). Depending on the extent to which it is diluted, the acrylic resists blending with the ink or merges with it to create a new gray tone. Like choosing to wield a paibi, the choice to incorporate acrylic into an ink painting has profound repercussions for the nature of Zheng Chongbin's art. He first tried using acrylic with ink in 1986, and he has described his motivations thus:

Initially when I picked up the acrylic, I was thinking about it from the material point of view. I felt the painting physically did not have enough impact, and I wanted to add more textures as well as other layers beyond pure water and ink wash. My idea was to add one more element and then see what happens-explore the possibilities.13

Zheng brushes a little water onto the border between the two xuan sheets, causing the forms to run together. Then he climbs a tall ladder to look down and consider the painting. He is almost finished with this painting for the day: it needs time to dry before the next step. On the second day, Zheng Chongbin turns over the first sheet. The ink has entirely permeated the thin paper, and the initial ink rectangle remains visible through the back as a ghost. Although the painting is close to its final form, Zheng continues to work on it for a couple more days. When he is finished, the first sheet is tilted and slightly overlaps the second, and they have come together in a rich unified composition. The whole will be mounted with a strong paper backing, whereupon the wrinkles will vanish entirely (fig. 3).

THE JOURNEY TO ABSTRACTIONWhen he was twelve, Zheng Chongbin began studying figure painting by copying the characters in narrative picture books called lianhuanhua 连环画. These inexpensive books were produced in huge quantity during the Cultural Revolution, some drawn by major artists: to bring stories of great communist heroes and martyrs to life for massive-scale public consumption was considered a laudable enterprise. Zheng learned to sketch in the Western realist manner and, admitted to the art academy, elected to study figure painting in the Chinese painting department. He found the curriculum limiting, later remarking:

For us in figure painting, there was not much choice. In landscape painting, a rock or tree has no particular shape. The generalized form is most challenging for figure painting. We had to understand anatomy, and also there were formulas. We all learned how to render an eye by laying down one brushstroke, then picking up a certain amount of water and putting it down: it spreads out and forms the pupils. Similarly, we knew how to paint lips, and how to add other layers of color or light ink to bring everything together. It was so dogmatic!14

This was the problem with figure painting. For subjects to be recognizable as figures, they required a certain amount of mimetic detail. An artist could take liberties with the brushwork describing a robe, for example, but the rendering of head and hands was tied to representationalism. Painters of flowers were less restricted, and landscape painters had the greatest freedom. In the classroom, Zheng Chongbin and his fellow students conformed to the precepts of the time, while outside of class they worked to break down the dogma, to find ways of putting all they had learned about both Chinese brushwork and Western chiaroscuro and modeling to play in the service of a new art. Around 1985 Zheng became fascinated with Surrealism.

The mid-1980s saw the rise of the '85 New Wave movement in art, catalyzed by an influx of information from outside China avidly devoured by young intellectuals. From 1966 until 1976, the year Mao died, China had endured the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Largely closed off from the outside world, the nation had been theoretically intent upon fulfilling the goal of continuous revolution. In reality, it was a time of destruction and persecution, with schools closed, families torn apart, educated youth sent to the countryside, books and art smashed and burned, and artists and intellectuals unwilling to conform harshly punished. By the early 1980s, the art academies and other schools had reopened and were filled to capacity, leader Deng Xiaoping had begun the process of integrating China into the world economy, and communication with the outside world was gradually increasing. At the art academies, not only was new information concerning Western art the subject of fascination, so too were the rapidly translated, newly available Western philosophical texts. Books by Freud, Wittgenstein, Nietzsche, and the like circulated among students. Socialist Realism and Maoist thought both had insisted that everything of value was readily apparent, available to all. Western philosophy and art proposed the opposite: a thriving inner world, amorphous at times, and not always easy to access. Ironically, the Cultural Revolution had encouraged people to keep their real opinions and feelings to themselves, so a philosophy and art that recognized the importance of the inner psyche struck a chord.

Zheng Chongbin's Water Bird Series (1986) (fig. 4, plate 2), Facial Type No. 2 (1987) (fig. 5, plate 4), Instrument No. 3 (1987) (fig. 6, plate 5), and Another State of Man No. 19 (1988) (fig. 7, plate 11) show the artist's gradual abstraction of figural imagery to produce a sense of the inner world in place of outer appearance. Interestingly, as Kenneth Wayne notes, "the early and transitional works of many of the American artists who became Abstract Expressionists have distinctly surrealist elements to them..."15 Zheng found the same route from realism to non-representationalism as did the European and American artists of the twentieth century: passing through Surrealism and abstraction on the way.

Zheng Chongbin's 1980s surrealistic paintings were followed by his Blot series, which explored a basic vocabulary of abstract forms arrayed within a shallow plane (fig. 8). An increasingly sophisticated investigation of a kind of theatrical space posited behind the picture plane followed. In such works as the Matrix series, Zheng inserted abstract forms in that space, drawing on diverse sources including his experience as a figure painter, his knowledge of early monumental Chinese landscape painting, and his interest in sixteenth-century European Mannerist painting (fig. 9). He rendered the abstract forms wielding a brush.

Almost abandoning the brush in favor of allowing the media to follow a directed path, Zheng Chongbin arrived at non-mimetic painting in 2009. Through his decades of working with ink, white acrylic both dilute and non-dilute, and paper, he had achieved an intimate understanding of the physical properties of the materials, including their propensities to interact and the timeframes in which they do so. This deep knowledge allows Zheng to work with his materials in real time, directing the end result. Now that the paintings do not serve to represent anything, their reality is their relationship with the surrounding space and with the viewer: they tie the viewer and space together. The scale of the work creates an environment within which the viewer exists. This is notable in the case of the very large Field of Lines No. 1 (2013) (fig. 12, plate 43), but also is the means by which the more human-scale paintings, like Seduction (2012) (plate 30), Fall and Rise (2013) (fig. 10, plate 38), and Lines with Volume (2011) (fig. 11, plate 27), function on the viewer. This matter of scale and relationship with the viewer is also a hallmark of mid-century modernism.

In Zheng Chongbin's paintings, black takes on a power and presence felt more frequently in nature than in art. In traditional Chinese painting, much is made of the compositional value of the paper left untouched by the brush. But that blank paper does not achieve the quality of light and life conveyed by Zheng's whites--either the white of the untouched paper or the white of the acrylic--because the blacks are not so all-consuming. The ultimate example of this is Dark Vein Nos. 1-2 (2013) (fig. 13, plate 42), whose majestic expanse of black splits open to reveal a streak of light: in nature all is black except that which is reached by light. The revelation of the white from within the black mirrors the human metaphysical search for meaning from within a vast unknown. Zheng Chongbin's use of black achieves such power because of his deep appreciation for its variety: he notes "it is not static black or simple black, but there is deep black, rich black, layered, level, and expressive black." Furthermore, "Ink is anti-meaning color. It is not about black, or about white, about all color, or about monochrome."16

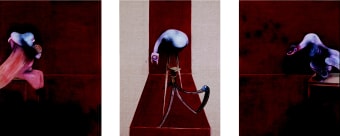

Having concentrated upon pure forms in space--both the space of the painting and the space within which the painting is sited--in his most recent works, Zheng Chongbin occasionally injects subtle secondary content. For example, Six Canons (2012) (fig. 14, plate 32) refers to the Six Laws of Painting (绘画六法 Huihua liufa) laid down by Xie He 谢赫 in the sixth century. Composed of six vertical panels reminiscent of the traditional hanging-scroll format, the work loosely references Xie He's precepts and provides a stage for the artist's ambitious rethinking of the laws for the twenty-first century.17 Triptych (2013) (fig. 15, plates 35-37) is inspired by a print version of Second Version of the Triptych of 1944 (1988) by Francis Bacon (British, 1909-1992) (fig. 16), whose deconstructed figural forms have long struck a chord with Zheng: this work required a return to the brush, and integrates Zheng Chongbin's earlier abstracts with his current focus on the relationship between the work of art and the surround- ing space, which it embraces through the form of a set of three hanging scrolls.

TIES ACROSS TIME AND SPACEOn his path to non-mimetic painting, Zheng Chongbin emphasized several factors that also have taken center stage in the writings of Shitao and of the American mid-century modernists. The affinity between the three is striking and unavoidable. First, Zheng and Shitao, as well as at least some of the mid-century modernists, agree that the artist receives something from nature, and through the artist as conduit that something is transformed into art. There is a direct transformation that is not routed through or interpreted via a verbal understanding. And most important, these artists all emphasize the degree to which the chosen media are the work of art. The intrinsic qualities of the media drive the form of the final creation. The ink or paint is recognized as primary, paired with the manner of application. As the painter Hans Hofmann (American, born Germany, 1880-1966) put it, "Creation is dominated by three absolutely different factors: first, nature affects us by its laws; second, the artist who creates a spiritual contact with nature and with his materials; and third, the medium of expression through which the artist translates his inner world."18

In his theoretical text Huayulu 画语录 (Remarks on Painting, c. 1700), Shitao wrote:

The Perfected Man must be universal and enlightened... He perceives things beyond their material forms, and when composing those forms, he reveals no trace of his efforts. Ink seems applied as if the painting were already created; brush movements appear to result from spontaneous activity. A scroll of a few feet can contain a landscape with all things between Heaven and Earth. Yet the mind is as placid as if in a state of total emptiness 愚者与俗同识... 受事则无形。治形则无迹。运墨如已成。操笔如无为。尺幅管天地山川万物。而心淡若无者.19

Both Hofmann and Shitao extoll the spiritual union between artist and nature, and artist and materials.

Zheng Chongbin believes of Shitao that he considered the "mindscape" was only the surface rather than the content of the materialization of the ink image. Comparing the media employed by the seventeenth-century master to that of the twentieth-century Abstract Expressionist Ad Reinhardt (American, 1913-1967), he writes:

Shitao's blacks and Ad's blacks are the black of the black noumenal language and the black of aesthetic wisdom. They are also reified black. In [the Huayulu] "Chapter on Brush and Ink" we glean a premonitory feeling that enlightenment can be visually experienced through the independent material states of the ink body.20

This latter statement describes a core provision of Zheng's art. In his view, "the convergence of contemporary art and traditional ink is not only an exploration of media but also a choice of perceptive vision. This choice is a proposition about how we contemplate the parameters of painting."21

CONCLUSIONZheng Chongbin's oeuvre returns art language to its long-hallowed position of centrality in Chinese ink painting. In so doing, his works also accomplish a tight dialectical fusion and evolution of East and West. Zheng's path to attaining such results has required many years of simultaneously deconstructing the language of ink painting and plumbing the philosophical and practical depths of Western modernism. Now fifty-two years old, at mid-career he has established a new platform for ink painting, explicated by his essays on painting theory and embodied by his works. One difficulty inherent to such a revelatory achievement is the problem of positioning: does his art belong to China or to the West? While in the West it tends to be seen as Chinese because of the medium, in China it often is viewed as non-Chinese or Western due to its departures from the ink-painting mainstream. The strength of the urge to position Zheng Chongbin's paintings as either Chinese or Western should be acknowledged as a signal of the strength with which his oeuvre embodies selected values of both. But the urge must then be put aside as a distraction from the important concepts expressed by Zheng's painting, and the profound aesthetic experience offered to those who choose to avail themselves of it.

As art critic Harold Rosenberg (American, 1906-1978) said, "The aim of every authentic artist is not to conform to the history of art but to release himself from it in order to replace it with his own history."22 Zheng Chongbin has found a new direction for art, with a new way forward both for abstraction and for ink.

NOTES1. Shitao, Huayulu, chap. 7, in Enlightening Remarks on Painting, trans. and with an introduction by Richard E. Strassberg (Pasadena, CA: Pacific Asia Museum, 1989), 97. 2. Alexandra Munroe, The Third Mind: American Artists Contemplate Asia, 1860-1989, exh. cat. (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2009). On view January 30-April 19, 2009. 3. Michael Sullivan, The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art from the Sixteenth Century to the Present Day (London: Thames and Hudson, 1973). 4. Kobena Mercer, ed., Discrepant Abstraction (London: Institute of International Visual Arts / Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006). 5. See, in this volume, Craig Yee, "The Classical Origins of Contemporary Abstraction," 2013. 6. Selden Rodman, Conversations with Artists: 35 American Painters, Sculptors and Architects Discuss Their Work and One Another with Selden Rodman (New York: Capricorn Books, 1961). Quoted by Maria Popova, "Jackson Pollock on Art, Labels, and Morality, Shortly Before His Death," Brain Pickings, April 9, 2013, http://www.brainpickings.org/index.php/2013/04/09/jackson-pollock-selden-rodman-conversations-with-artists/ (accessed June 6, 2013). 7. Susan Bush, The Chinese Literati on Painting: Su Shih (1037-1101) to Tung Ch'i-ch'ang (1555-1636) (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971), 32. 8. The Dao 道 (literally "the Way") is a metaphysical concept relating to harmony with nature or the essence of the universe. 9. The form of landscape most revered in Chinese art history is not a literal representation of the natural landscape; rather, it is a reflection of the mind of the painter. 10. This section is inspired by Elaine de Kooning, whose many wonderful essays titled "[Artist's name] Paints a Picture" brought their creative processes to life for readers. The creation of the painting I describe by Zheng is documented in The Enduring Passion for Ink: A Project on Contemporary Chinese Ink Painters 墨咏: 当代水墨画家系列 [Moyong: dangdai shuimo huajia xilie] 10-part film series, digital, color, sound, 2012-13, directed and produced by Britta Erickson, on contemporary Chinese ink painting. For further information, contact Erickson.britta@gmail.com. 11. Mu Yilin had studied with the great Shanghai scholar-painters of the age, such as Xie Zhiliu 谢稚柳 (1910-1997) and Cheng Shifa 程十发 (1921-2007). Chen Jialing, Zheng's second teacher, had been a student of Pan Tianshou 潘天寿 (1897-1971) and later Lu Yanshao 陆俨少 (1909-1993). Zheng thus can claim a place in the long lineage of Chinese scholar-painters. 12. Zheng Chongbin, interview with the author, conducted in the artist's studio in San Francisco, October 20, 2006, published in Britta Erickson, "Innovations in Space: Ink Paintings by Zheng Chongbin," in Chongbin Zheng: Ink Painting (Shanghai, 2007), 28-31. 13. Ibid. In addition to white acrylic, Zheng has experimented with employing fixer to add new layers to his paintings, but he has not used fixer since 2010. 14. Zheng Chongbin, interview with the author. 1S. See, in this volume, Kenneth Wayne, "Zheng and Abstract Expressionism: An Introduction," 2013. 16. See, in this volume, Zheng Chongbin, "A Reordering of Xie He's Six Laws," 2013. 17. Ibid. 18. Hans Hofmann, Search for the Real, ed. Sara T. Weeks and Bartlett H. Hayes, Jr. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1967), 55. 19. 愚者与俗同识... 受事则无形。治形则无迹。运墨如已成。操笔如无为。尺幅管天地山川万物。而心淡若无者。Shitao, chap. 16, in Strassberg, Enlightening Remarks on Painting, 85, 102. 20. See, in this volume, Zheng Chongbin, "My Reading of Shitao's Remarks on Painting," 2013. 21. Ibid. 22. Harold Rosenberg, Art on the Edge: Creators and Situations (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975), 64.

|

Establishing Spirit in the Sea of Ink: Zheng Chongbin from Impulse to Form

Britta Erickson