|

In the Zoon-Beijing Bio series, Huang Zhiyang 黄致阳 uses the traditional materials of ink and traditional brush on silk to depict the human-scale world of plants, animals and other forms of organic life. Like the monumental landscape painters of the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE), Huang works on a grand scale to depict the life-generating power of the natural world. Unlike the ancients, however, Huang uses the living organism (生物 shengwu)-as opposed to the landscape-as the primary metaphor for this life-generating power.

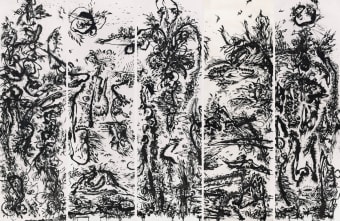

In the monumental, wall-sized work Zoon-Beijing Bio: Spring No. 1 (2013), Huang divides his composition into five areas (fig. 1). Quasi-human figures stand upright in the far right and left sides of the horizontal composition while a third figure occupies the space toward the center. Huang describes not the outside appearance of these figures but rather reveals their inner structure, organ systems and energy flows-what the neo-Confucians from the Song dynasty would have called their 理 li, or pattern of coherence or order.

He accomplishes this using the traditional brush language of landscape 皴法 cunfa-individual brush strokes used to model the form and textured surfaces of rocks and mountain formations. Huang's "texture" stroke, however, is more than a means to depict form; it is an artistic element in and of itself-a primary unit of gestural expression that signifies a constitutive quantum of energy (气 qi).

To bind individual strokes into coherent forms (li), Huang deploys two complementary types of brushwork revealed here in this primordial form (fig. 2). The strokes at the center circle and cohere into a stable form-they embody the quality of stability (阴 yin). The strokes on the outside, in contrast, expand and radiate outwards-they embody the quality of movement (阳 yang). Huang's figures are all made from these strokes (i.e. are made from the same "stuff" or qi)-their form emerging from contrasting and counterbalancing forces dispersing and expanding in one place (fig. 3) and cohering and condensing in another (fig. 4).

Like the outward expansionary force of stellar fusion and the inward contradictory force of gravity, two complementary forces in balanced configuration and dynamic interplay naturally and spontaneously produce transient form that is stable over a period of time. The configuration of forces that give form and coherence to flows of energy (qi), the Chinese philosophers called li or "the principles of order/pattern/coherence."

Unlike previous single-panel works in his earlier Phallicism, Maternity Room or Zoon-Beijing Bio series, Huang situates the figures in Zoon-Beijing Bio: Spring No. 1 (2013) within a landscape of rocks and mountain forms and other forms of macro-organismic life such as plants (fig. 5), birds (fig. 6), and insects (fig. 7). The same can be found in his even bigger Zoon-Beijing Bio: Spring No. 1 (2014), currently on display at the National Museum of China (fig. 8).

Huang's bio-organismic reality is an interwoven one in which the patterns li of life forms merge and co-emerge-a shoulder morphs into the wild plumage of a bird (fig. 9), a leg grows into a flowering stalk (fig. 10). Life forms, furthermore, merge not only with each other but co-emerge with the landscape itself-a forested mountain grows from one figure's body (fig. 11), the sun transforms into a flying bird (fig. 12). In Huang's view, all life is emergent from a generative and fecund world and co-evolves within a panoply of other life forms; Man does not stand apart from Nature but is rather a part of and the product of Nature.

In terms of Chinese philosophy, this unfolding of multiplicity and diversity (i.e. the emergence of all existent forms or 万物 wan wu) is precipitated by the generative forces of 乾 qian-male energy which is creative and responsible for all difference and variation-and the conserving forces of 坤 kun-female energy which is completing and responsible for the generation and continuation of all form. When qian and kun come together, reproduction over countless generations gives rise to the repetition and proliferation of distinct forms of life (i.e. reproductive isolation produces speciation). These principles are biologically well-grounded and it is worth noting that if we add selection to generation, difference and repetition, we get Darwinian evolution.

Note: As it turned out, the Chinese philosophers did overlook the concept of selection and instead envisioned an ever-complexifying natural world in which a symbiotic harmony of wills governed relations between species. The introduction of the idea of natural selection in the late nineteenth century was thus a rude shock that precipitated an existential crisis amongst Chinese intellectuals who feared that the weaknesses of Chinese culture could lead to the extinction of the Chinese civilization. It turns out that the scientific world would need to wait another hundred years for the evolutionary micro-biologist Lynn Margulis to vindicate the Chinese concept of symbiotic harmony as a force at least as powerful as selection in the history of life's evolution on earth. |

Huang Zhiyang: Zoon-Beijing Bio

Craig Yee

, 2013, ink on silk, 5 panels, each 475 x 120 cm.jpg)

, 2013, ink on silk, 5 panels, each 475 x 120 cm(1).jpg)

, 2013, ink on silk, 5 panels, each 475 x 120 cm(2).jpg)

, 2013, ink on silk, 5 panels, each 475 x 120 cm(3).jpg)