|

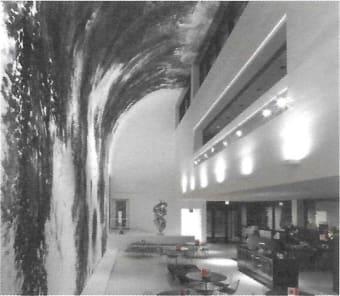

Bingyi made the monumental ink painting Cascade through an unusual process that appears to be aligned with land art and performance art. She spread sheets of rice paper, covering an area sized 20 by 13 metres, across a basketball court in the small village of Xiuli in southern Anhui province. The crew, led by the artist, worked at night in order to avoid the scourging sunshine during the day and used only the headlights of a running car for illumination. Bingyi poured ink mixed with water and household chemicals onto the paper as though it were a choreographed act. At times she painted like she was dropping a stone into still water, wetting the paper within a split second, resonating Bai Juyi 's verse from the Tang dynasty, "Big pearls falling into the jade plate of small pearls." At other times, Bingyi caressed the paper with a brush like a pipa player lightly plucking the strings of her instrument. Through this process, different layers of ink materialized into an enormously rich mixture of texture and colouration. This seemingly infinite landscape is now attached to the vault of the atrium of the Smart Museum at the University of Chicago. Like an unleashing of power spewing out of the haze, this painting installation captures a sense of the chaotic state of the world. At first sight it is difficult not to be amazed by the massive painting as a whole, but, after a closer look, one is drawn in and even more moved by its imposing details.

Cascade depicts a gigantic waterfall that seemingly soars into the sky, against the laws of physics. Although it clearly reflects upon the classical notion of Chinese landscape painting, the work evokes one's emotional and intellectual relationship with one's context. In the recent practice of contemporary Chinese art, Bingyi is notable for her consistent attempt to build a critical relationship with the classical past, and for her focus on the universal values of beauty and emotion. Moreover, she is engaged with building a meaningful phenomenology of the specific physical environment and medium in each of her projects.

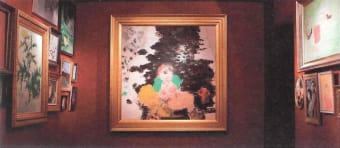

Her non-academic background (she received little training as an artist) and studies of Western and Chinese art history give her an unconventional approach to painting. In 2009, Bingyi created Seamlessly Lost, a 40-metre-long oil painting on canvas whose surface was punctuated by wave-like folds, which was recently on view at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, in Buffalo. In the same year she created an impressive salon of fantastical paintings, SKIN, at Contrasts Gallery in Shanghai. She does not produce painting with the same theme repetitively, nor does she paint in the same style, What makes these painting projects engaging is the conceptual scheme embedded within them: gallery sales for Seamlessly Lost were achieved by the audience cutting out, as if it were a piece of fabric, the section they wanted, whereas SKIN proposes that there are only two characters in our social system—you and I—and that the only maneuvering factor between these two characters is SKIN.

In the case of Cascade, Bingyi raises a number of provocative questions about the medium of ink painting. For instance, to what extent does this installation follow the tradition of ink painting, or, more specifically, landscape painting? One may argue that she views shanshui painting as the visualization of the world, and as an embodiment of her mind. Ancient philosophers from East to West share the belief that water is a primal force within the universe. For example, Guanzi, a renowned Chinese philosopher from the Spring and Autumn period (771—403 BC) , wrote in his Guanzi chapter "Water and Land," "What is water? It is the source for the tens of thousands of species, and the origin for all lives." Similarly, Greek thinker Thales (ca. 635—543 BC) also believed that water forms the basis of the world. In other words, Bingyi is clearly making a philosophical commentary on the relationship between water and ink, turning the actual medium of the painting into the subject of the painting.

Alternatively, one may argue that this painting carries no obvious evidence of brushwork, no traces of cunfa (the Chinese term for methods of painting line and texture, which has dominated the discourse of Chinese painting since the Song dynasty), and that Bingyi has no interest in building distance or space in the picture plain. The artist uses ink as a substance in tandem with chemical reactions in accordance with the movements of earth, wind, and moisture, but not as a practice that connects every mark to the history of the ink painting tradition. Standing in the atrium of the Smart Museum, one feels that Cascade disappears into the architecture of the building, in which the vault of the space surfaces behind the painting. Hence Cascade presents more than the dancing movement of ink: It is about the specific site of the original performative action that took place in Xiuli and its juxtaposition with an exhibition space at the center of a Western art institution.

Before Bingyi decided to conduct the painting of Cascade in the Huizhou area, where the Xiuli village is located, she traveled for a year to various mountains in search of an ideal site. The region of Huizhou was the birthplace for the Xin'an school of painting during the seventeenth century Xin'an school painters rejected the conservative academicism of the Four Wang Masters and argued for painting from nature and life. The leading figure of the Xin'an school, Huang Binhong, wrote that the artist should acquire inspiration from direct contact with mountains and water. As an artist who is willing to travel vast distances in search for inspiration, Bingyi selected the home region of the Xin'an school not by accident, but by choice.

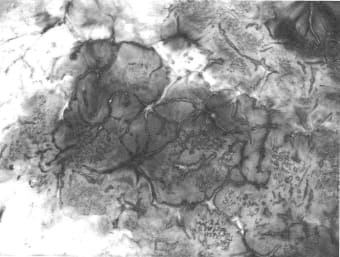

Bingyi chose to work in the same spirit as the Xin'an masters because notions of style and technique are not her primary concern. Her goal is to cultivate an intellectual connection to painting as an act, and to build a transcendental understanding of the problematic nature of history. On the one hand, Cascade shows what possibilities ink as a medium can bring to rice paper. It demonstrates the state of mind that classical Chinese intellectuals have held in esteem since ancient times, all of which seem to stay within the history and condition of China. However, the infinite variation and subtlety that make this enormous painting so impressive show little trace of controlled touch by the human hand. As the creation of Cascade took place at night, Bingyi was able to generate unexpected results through a kind of randomness. Moreover, she used the slope of the land and chemical reactions as critical incentive for her final composition. Tied in with this is Bingyi's belief that the fundamental connection between the individual and the universe is perpetually uncertain and filled with the unexpected. This lack of certainty that is embodied in the painting reflects the deep-seated existential attitude of the artist.

Bingyi has written that Cascade depicts water in its various forms—from a running stream, to cloud formations, fog, ice, and even human tears. Yet one could view the metamorphosis of water above earth as the movement of the atmosphere and the evolution of species throughout history. Within the smaller details of the painting, the notion of change is expressed through the process of chance and a sense of vastness and variation that arises from it. The saturation and distillation of ink that responds to the flow of water constitute a physical process that could be seen to resemble growth in nature. To the ancient painters, the mixing of ink and water represented the interaction between different currents in life. In Cascade, painting imitates a dynamic process that progresses from order to chaos and, paradoxically, from complexity to simplicity, both conducted through discipline and randomness, eventually approaching a massive void of existence. On this note, Cascade has little to do with the New Literati painting, experimental ink painting, urban ink painting, or abstract ink painting. It instead concentrates on the notion of the entropy-like chaos in metaphysics. Her practice of travel and painting on site is precisely about discovery: both of one's personal connection to that chaos and of one's expression about that chaotic state.

Bingyi holds no brush in her hands, but she is able to hold thousands of rivers and mountains in her mind. In between each splash of ink and water, grandiose entropy occurs. If Dong Qichang, a prominent painter, theorist, and collector in the Ming dynasty, came back to life, one may wonder how he would respond to this magnificent painting. Would he be mesmerized by the making of the painting? Or would he wonder if his theory of brushwork and metaphysics could be applied to it? We will never know, but the painting stands.

Source: Yishu Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, Volume 10, No. 4, July/August, 2011. Reprinted in Art and Investment, Volume 10, 2011. |

The Metamorphosis of Water: Bingyi's Cascade

WEI XING