Observing My Distant Self: Kang Chunhui

“Observing My Distant Self: Kang Chunhui” marks the artist’s premiere solo exhibition at INKstudio, offering an immersive journey into a crucial juncture in her artistic development. The exhibition unfolds in two distinct sections: “Observing My Distant Self” and “Undeniably Me”.

Observing My Distant Self

“I found myself in a landscape reminiscent of the Western Regions, particularly the ancient city Loulan that has long since vanished. I stood atop a hill, observing my distant self—undeniably me—I turned to the setting sun.” ——Kang Chunhui

Almost an enigmatic prophecy, the vivid childhood dreamscape lingered in the subconscious of visual artist Kang Chunhui (Urumqi, Xinjiang, 1982) for over three decades, until last year, 2023, when the time came for her to revisit its mystique with renewed urgency.

Occupying the entirety of INKstudio’s ground floor, Observing My Distant Self 73°40′E~96°23′E 34°25′N~48°10′N, 2019-2023, is an expansive eight-part multimedia project responding to Kang’s childhood dream in the form of a metaphorical pilgrimage to the Western Regions. Eight 6’6”-long videos place an aspect of Kang’s artistic practice in spatial dialog with a location in Xinjiang selected by Kang for its historical, sociological, and cultural significance. On her pilgrimage Kang makes eight stops: the Kumtag Desert, Lop Nur, Bosten Lake, Tarim Poplar Forest, Kuqa Old Town, Tianshan Grand Canyon, Kizilgaha Beacon, and the Kizil Caves. Lop Nur, for example, is a historically- and archaeologically, multi-layered socio-cultural site situated at the far east shore of the post-glacial Tarim lake. From around 1800 BC until the 9th century, the lake supported a thriving Indo-European Tocharian culture. The Buddhist monk Faxian (337-422) went by the Lop Desert on his way to the Indus valley as did Marco Polo (1254-1324) in his travels along the Silk Road. A former salt marsh, Lop Nur has run dry as a result of dam construction and, over the past hundred years, has been variously a site of large-scale, industrial mining, a contested site of ecological restoration and the military test site where China detonated its first atomic and hydrogen weapons. Throughout her journey, Kang explores the boundaries between place, history, memory, self and creativity, conceiving them not as rigid territories but as expansive areas for exploration, exchange, synthesis and transformation.

Undeniably Me

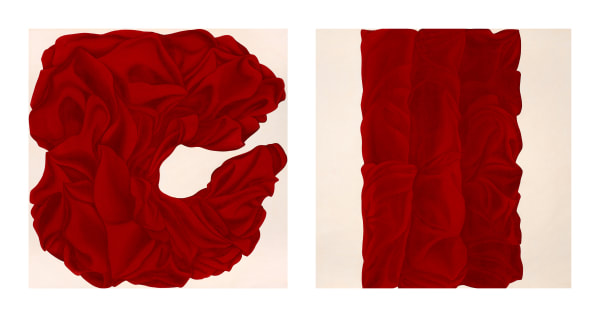

On INKstudio’s third floor, Kang debuts new works in her Post-Modern synthesis of historical Central and East-Asian polychrome painting styles. In Kang’s latest works in her signature Sumeru series, she continues her alchemical exploration of mineral and organic red pigments through the form and metaphysical theme of the fold. In The Hidden Protagonist No. 2, 2022-2024, she transcends the boundaries between Imperial bird-and-flower and religious figure painting while exploring resonances between Eastern and Western mythologies. In The Hidden Protagonist: Mount Fuchun she transgresses the traditional boundary between xieyi or “calligraphically expressive” and gongbi or “meticulously descriptive” painting while interrogating the dialogical relationship between self and history through the landscape.

Pigments and Alchemy

Having been trained in Chinese traditional gongbi or “meticulous brush” painting since her youth, Kang Chunhui stands out for her thorough exploration and contemporary reinterpretation of the Buddhist mural iconography and color schemes found in the Kizil Caves near her hometown of Urumqi. Kang perceives the colors of such religious murals as profoundly other-worldly, bearing the weight of time and evoking an awe for life, death and the space in between, they express our most intense spiritual emotions such as yearning for the afterlife or unwavering faith.

The transmutation of land into pigment into art is central to Kang Chunhui’s revival of Central Asian religious painting. Unlike other artists who purchase their mineral pigments already compounded, Kang researches and compounds her own mineral pigments from the same local sources used by the Central Asian artisans working in and around the Kizil Caves. Kyzil in Uyghur means “red” and the resulting brilliant red hues, obtained by mixing minerals from the land and organic cochineal pigments evokes a textural sensation akin to velvet and a depth of color that far exceeds anything achievable in the media of oil or acrylic.

Sumeru

In her Sumeru series, Kang explores the relationship between color, shape, light, dimension and boundary through the form of the fold. Folds of draping fabric are a key artistic element in Gandharan Greco-Buddhist sculpture and form the basis for the brush-line mode of early Chinese figure painting that later becomes the sine qua non of East Asian brush painting. In Kang’s treatment of the fabric folds she utilizes not line and outline but the color and shadow characteristic of South Asian, Central Asian and Hellenistic polychrome painting as the primary means of modeling form. The red and white that she uses are, in fact, compounded from minerals sourced from the same sites used by the Kizil Cave artisans and it is through her fine control of the compounding and blending of mineral and organic cochineal pigments that Kang achieves the chromatic gradations she utilizes to model the forms of her folds. It is worth noting that Sumeru refers to the sacred five-peaked mountain of Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist cosmology. The fractal-like architectural structures of the Buddhist pagoda and temple complexes such as Angkor Wat (12th Century) and Borobudur (9th Century) are realizations of the unfolding metaphysical vision symbolized by Sumeru anticipating by a millennium Giles Deleuze’s writings on the Fold in the metaphysics of Leibnitz and the Baroque.

Mythology and the “Hidden Protagonist”

In addition to her alchemical exploration of pigments, Kang Chunhui’s works are replete with symbolic, philosophical, and mythical references from seemingly disparate cultural traditions—what she refers to as her “hidden protagonists.” Kang’s Post-Modern syncretism of religious and mythological imagery reflects the historical, pre-modern emergence of a trans-natural religious pictorial art first in South Asia in 2nd Century B.C.E. Ajanta and its subsequent transmission to the Hellanistic Central Asia kingdoms of Sogdiana and Bactria with the spread of Buddhism. This artform then entered China in the 3rd-12th Centuries through the transmission of Buddhism along the Silk Road and subsequently evolved into the Imperial painting styles of the Tang (618-907) and Song (960-1279) courts. From China, it then spread to Korea, Japan, Tibet and Southeast Asia—again through the dissemination of Buddhism—and back to Central and South Asia through a combination of Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) conquest and cultural exchange with the Moghul and Ottoman courts.

This early trans-national pictorial language has taken modern and contemporary form during the art reforms of Meiji-era Japan—Nihonga—through the postcolonial, post-modern revival of the Persian/South Asian miniature by contemporary South Asian artists such as Shahzia Sikander (b. 1969, Lahore) and Imran Qureshi (b. 1972, Hyderabad), through the post-Mao revival of Imperial Court painting by Chinese artists such as Xu Lei (b. 1962, Nantong) and Hao Liang (b. 1983, Chengdu) and through the contemporary thangka-inspired paintings of Tibetan artists such as Tenzing Rigdol (b. 1982, Kathmandu) and Gonkar Gyatso (b. 1961, Lhasa). Kang Chunhui’s contribution to this unfolding, post-colonial discourse takes us back to the eventful, pre-colonial moment when this early trans-national, religious pictorial language first entered China at Kizil and subsequently evolved into the secular, poetic art of Imperial bird-and-flower painting.

The Hidden Protagonist No. 2

Started in 2022, prior to her journey to Xinjiang, the diptych, The Hidden Protagonist No. 2, was completed in 2024 after three years of meticulous development. Kang conceives each of her paintings in terms of material, technique and emotion. This monumental diptych employs both organic and mineral pigments—in one panel, blue and green pigments predominate, in the other red and yellow. Technically, Kang integrates her mastery of custom compounded pigments with the subtle color washes and meticulous brushwork of Imperial bird-and-flower painting. Concealed within the multi-layered folds of floral blooms and avian feathers, however, are two human figures—Kang’s “hidden protagonists.” The first, rendered in blue, is Sandro Botticelli’s Saint Sebastian, 1473; the second, rendered in red, is the same author’s The Birth of Venus, 1484-1485. Venus embodies birth and life, while St. Sebastian personifies the figure of the dying martyr — one represents an unorthodox and enigmatic path to existence, while the other embodies death and the tragedy of sacrifice. Although the images are drawn from European art, for Kang her “hidden protagonists” are at once personal and universal. Venus, for example takes Chinese literary form as Luoshen or “The Goddess of the Luo River”, a paragon of femininity rising from the river waters symbolizing personal freedom and liberation.(i) Saint Sebastian, on the other hand, finds resonance with Six Steeds of the Zhao Mausoleum in which six horses, their bodies pierced by arrows, offer themselves willingly for their master. (ii)

The Hidden Protagonist: Mount Fuchun

In Kang Chunhui’s newest major work, her “hidden protagonist” is the towering Yuan Dynasty literati painter Huang Gongwang (1269-1354) and his iconic masterpiece Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains. Unlike her homage to Boticelli which transcends form—flower and figure—and mythology—European and Chinese—Kang’s assault on the sacred ground of the Fuchun Mountains is pure transgression, albeit very soft in manner. Her approach is deeply empathetic: she seeks to understand what Huang Gongwang envisioned at 80 years old when he executed his masterwork perceiving in it a longing for an idealized place beyond this life’s reach. Following in the tradition of Dong Qichang (1555-1636), the late Ming Dynasty literati art theorist, calligrapher, and painter who suggested that artists journey to the locations of ancient masterworks not so much to directly engage with nature but, rather, to gain deeper insight into the mindset and inspiration of the old masters, Kang made a pilgrimage to the Fuchun Mountains in March, 2024. Walking around the entire Fuchun River and exploring the landscapes around Hangzhou and Wuxi, however, Kang discovers not Huang Gongwang’s inspiration but her own: “Sensing my surroundings deeply, it's as if every element in that place imparts its own unique essence onto me. Whether it's the rain and mist, the morning and evening light, or anything else, each contributes to this shared feeling.” (iii)

The resulting landscape is identical in scale to the original and follows faithfully its contours and compositional rhythm. In all other aspects, however, Kang’s homage to Huang Gongwang is quietly and emphatically a transgression. As early as the Five Dynasties (907-960) and Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127), artists began rendering landscapes in ink monochrome symbolizing serious matters of Neo-Confucian philosophy, statecraft and politics. Kang Chunhui, on the other hand, renders her composition in subtly modulated tones of pink and magenta. Huang Gongwang, along with other literati artists of his time, also rendered landscapes using calligraphic brushwork or cunfa as the landscape became a vehicle for autographic or xieyi self-expression.

Kang Chunhui, in contrast, employs the supposedly descriptive graded colors and brushwork of a gongbi artist to render her self-expression in a manner no less autographic. Whereas Huang Gongwang renders solid mountains and upright trees with his calligraphic brushwork, Kang Chunhui depicts prostrate petals and folding bloom forms using softly-graded color wash. We yield to her transgressions because we are convinced by the painting itself—the result is luminous and radiant, deeply familiar and yet utterly new.

But make no mistake, this is a young woman visual artist born in Urumqi and educated in Seoul who has entered the hallowed grounds of the literati landscape—populated since its inception exclusively by men—to assert herself as a contemporary woman artist with an uncompromising, distinctly feminine vision. She describes her approach as a form of homage, not to the masters of the past, but to her own emotional connection to nature itself. In the end, Kang Chunhui, undeniably herself, ends up her own “hidden protagonist.”

i. “洛神” (“Luoshen”) can be translated as “The Nymph of the Luo River” or “The Goddess of the Luo River”. It comes from a famous Chinese poem written by Cao Zhi (AD 192-232) during the Three Kingdoms period. A well-known depiction of the story can be found in a handscroll painting from the Song Dynasty, currently held by the British Museum.

ii. The Six Steeds of Zhao Mausoleum are six Tang Chinese stone reliefs of horses that were originally located in the Zhao Mausoleum, Shanxi, China. The Zhao Mausoleum is the burial site of Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty (618-907). The steeds were six valuable war horses ridden by Taizong during the early campaigns to reunify China under the Tang Dynasty.

iii. Kang Chunhui in an interview with the author in her Beijing studio, 27 April, 2024.

-

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, Observing My Distant Self: Kang Chunhui 73°40′E~96°23′E 34°25′N~48°10′N 凝视遥远的自己:康春慧 73°40′E~96°23′E 34°25′N~48°10′N, 2019-2023

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, Observing My Distant Self: Kang Chunhui 73°40′E~96°23′E 34°25′N~48°10′N 凝视遥远的自己:康春慧 73°40′E~96°23′E 34°25′N~48°10′N, 2019-2023 -

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, The Hidden Protagonist: Mount Fuchun 隐逸的主角:富春山, 2023-2024

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, The Hidden Protagonist: Mount Fuchun 隐逸的主角:富春山, 2023-2024 -

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, Sumeru No.21 (diptych) 须弥 No.21 (对屏画), 2023

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, Sumeru No.21 (diptych) 须弥 No.21 (对屏画), 2023 -

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, Sumeru No.25 须弥 No.25, 2023

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, Sumeru No.25 须弥 No.25, 2023 -

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, Collection of Clouds & Forests No.12 云林集 No.12, 2022

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, Collection of Clouds & Forests No.12 云林集 No.12, 2022 -

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, Collection of Clouds & Forests No.16 云林集 No.16, 2023-2024

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, Collection of Clouds & Forests No.16 云林集 No.16, 2023-2024 -

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, The Hidden Protagonist No.4 隐逸的主角 No.4 , 2024

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, The Hidden Protagonist No.4 隐逸的主角 No.4 , 2024 -

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, The Hidden Protagonist No.3 隐逸的主角 No.3, 2023

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, The Hidden Protagonist No.3 隐逸的主角 No.3, 2023 -

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, The Hidden Protagonist No.2 (diptych) 隐逸的主角 No.2 (对屏画), 2022-2024

Kang Chunhui 康春慧, The Hidden Protagonist No.2 (diptych) 隐逸的主角 No.2 (对屏画), 2022-2024