What is INKstudio?

INKstudio was founded ten years ago by three Stanford University alumni—business school classmates Craig Yee and Chris Reynolds and art historian and curator Dr. Britta Erickson—based on the simple observation that the world of global contemporary art was missing one of the greatest contributions any civilization has made to human culture: INK art. Central to our view is that INK is much more than a Medium; it is, in fact, a rich and complex artistic Language that expresses a similarly rich and distinctive Worldview—specifically, the civilizational worldview of China and East Asia.

Prior attempts at modernizing and internationalizing the INK language and, with it, the East Asian Worldview include important historical movements such as the Bokujinkai calligraphers in Post-war Japan and the Fifth Moon Group artists in 1960’s Taiwan, but it wasn’t until the post-Cultural Revolution 1980’s that China itself engaged in the difficult task of thoroughly deconstructing and modernizing the language of INK for the global reality that is China and the world today.

Since its founding, INKstudio has been focused on researching, documenting and exhibiting the individual practices of the most important artists of this post-Cultural Revolution period. We see each artist as an individual with his or her own unique and distinctive approach to deconstructing, reconstructing and transmitting the language of INK and the worldview it expresses. Each such artistic practice is thus a manifesto—a statement in action—about what INK art is at its most essential core. As a result, INKstudio, over the past ten years, has focused on producing solo exhibitions for these distinctively individual artists.

The current exhibition, Global INK, is our opportunity to share with everyone what we have discovered over our first decade of programming. It is not a group show but instead a special exhibition consisting of twelve separate solo presentations by twelve artists who we believe define the new global contemporary INK.

Transmission of INK

The language of INK art is both incredibly broad and incredibly deep and contains multiple, interwoven layers of signification and meaning. For example, in any particular work one might need to read brushwork, ink tone and texture, negative space on multiple levels, composition, subject and metaphor, text inscriptions, seal inscriptions, calligraphic style, painting style and seal carving style to name just a few dimensions of explicit communication. Furthermore, the ideas conveyed using this very deep and broad INK language cover philosophy, literature, religion, politics, history, art history, personal self-cultivation, metaphysics and many other domains all depending upon the particular interests of each artist.

Some contemporary INK artists preserve the breadth and depth of this received language and use it to create contemporary consummate masterworks that directly link the two-thousand-year history of INK art in China and East Asia with the global reality we live in today. The Beijing- and Tianjin-based figure artist Li Jin (b. 1958) for example, employs traditional figure painting and portraiture to capture our present, collective social consciousness. The Taiwan-based painter Peng Kang-long (b. 1962) integrates the formerly separate genres of Landscape and Flower painting to open up new possibilities for exploring our personal relationship to the natural world. The Hangzhou-based calligrapher Wang Dongling (b. 1945) takes the language of INK art into the public sphere through his ground-breaking integration of calligraphy, text and performance. Finally, the Nanjing-born landscape artist Liu Dan (b. 1953) undertakes the still unresolved challenge of integrating Northern Song composition with literati brushwork using methods from figure drawing and fresco painting. Although all four artists transmit the original language of INK, they do so not by preserving it unchanged, but by creatively transforming it into a contemporary form that is fully reflective of both our time and our globalized reality.

Deconstruction of INK

An alternative artistic strategy for dealing with the breadth and depth of China’s received INK language is to “deconstruct,” take apart or reduce the language to one or a few interconnected aspects of the original language. From this reduced or deconstructed language, the artist is then free to more deeply explore one aspect of the language and the focused worldview that this one aspect illuminates. Although much of the richness of the original language is lost through elimination and reduction, this process often provides us with a clearer conceptual understanding of the constituent elements of the original language. The conceptual clarity also makes it much easier to map or translate the insights gained from these practices onto concepts and practices current in international contemporary art contexts or even contexts outside of art such as science, philosophy and religion.

For the seminal exhibition of global contemporary art les Magiciennes de la Terre at the Centre Pompidou in 1989, the Guangdong-born, Paris-based visual artist, Yang Jiechang (b. 1956) in his Hundred Layers of Ink, reduced calligraphy to a daily cultivation practice of accumulating one layer of ink upon another. The Sichuan-born landscape painter, Li Huasheng (1944–2018) similarly, developed an INK-based cultivation practice only using the painting of brush lines rather than the layering of ink as the core process of INK art language. The Shanghai-born, California-based visual artist, Zheng Chongbin (b. 1961), takes a different approach deconstructing the language of bimo by eliminating the brush in order to clarify the immanent properties of INK as a dynamic and creative form of matter in itself. His focus is not on the artist as subject but rather on Nature—in the material form of INK—as both subject and creative agent. Finally, the Beijing-based conceptual artist Xu Bing (b. 1955) in his Landscript series deconstructs the relationship between Language (written characters) and Nature and between Nature and Art to then reconstruct a new relationship between Language and Art.

(Re)construction of INK

A third artistic strategy involves (re)constructing INK into a new linguistic configuration that parallels the breadth and depth of the original INK language but which articulates or makes visible a worldview previously unseen. For some artists, reconstruction follows naturally from deconstruction such as in Xu Bing’s case where his deconstruction of first writing and then painting led to a reconstructed system of painting using writing. The tremendous value in reconstruction strategies is that they dramatically extend the possible worldviews that we can explore and articulate using the constituent elements of our original INK language.

The Liaoning-born, Hangzhou-based woodcut artist and painter Chen Haiyan (b. 1955) takes the traditional elements of literati painting—including brush painting, calligraphy, literary writing and seal carving—and transfers them to her native medium of the woodcut in order to archive and share her world of dreaming. The Shanghai-based visual artist Wang Tiande (b. 1960) explores the themes of cultural destruction and restoration by reconstructing sophisticated, art-historical traditional landscape compositions made from materials—both found and created—modified or “destroyed” through burning, cutting, covering or appending. The Taiwan-born, Beijing-based painter and sculptor Huang Chih-yang (b. 1965) first reduces INK painting to its simplest element—the landscape brushstroke or cunfa—then systematically reconstructs an entirely new language of painting and sculpture which integrates both ink and mineral pigments, figuration and abstraction, and embodied experience and metaphysics. The Beijing- and Los-Angeles-based polymath Bingyi (b. 1975) employs contemporary scholarly research, literary writing and poetry, calligraphy and painting, video and film-making, installation and performance and site-specific land-and-weather art to reconstruct, in our time and from our global perspective, the intellectual, spiritual and cultural world of literati artistic practice.

Epilogue: Social Actors

In our first ten years, our program at INKstudio actually extended beyond these three strategies to include artists who use INK in a way largely unrelated to its original linguistic form. These artists create contemporary art in the mode of a social actor or Beuysian social sculptor—a mode completely alien to pre-Modern Chinese or East Asian culture. Through research-, performance-, installation-, and social sculpture-based practices, these artists demonstrate the enormous potential of INK and its related classical arts—such as writing, ritual, and music—to effect transformative societal change through socially- and sociologically-grounded art making. The Chengdu-based performance artist Dai Guangyu (b. 1955), the Yunnan-born, Beijing-based performance artist He Yunchang (b. 1967) the Hunan-born, Beijing-based feminist visual and installation artist Tao Aimin (b. 1974), and the Beijing-based language conceptual artist Jiao Yingqi (b. 1956) are four artists for whom INKstudio has either organized solo projects in the past or hopes to do so in the future.

Due to limitations in our exhibition space, we were not able to include these artists in the current show. Leave no doubt, that these artists represent a critically different approach to using INK and other related classical arts—such as language and ritual—to create critical, socially-engaged art from an East Asian cultural perspective. Over the next ten years, we expect these artists will be the subject of intensive study and curation not just at INKstudio but at public institutions both inside China and across the globe.

The Future

Naturally, any retrospective exhibition leads us to ask what the future holds. With the addition of forty-year Sotheby’s veteran Mee-Seen Loong to the INKstudio management team, INKstudio has ambitious plans to partner with museum institutions, corporate sponsors, curators, scholars, and private collectors to promote INK art globally in North America, Europe and the Middle East, regionally in Japan, Korea and Southeast Asia, and, most importantly, right here in the birthplace and current center of INK art worldwide—China. How we do this is not just a question for INKstudio as a gallery but for Chinese people globally who care deeply about the future of art and culture within China and China’s centrally important role in the creation of a global culture that respects and embraces both the commonalities and differences between our many respective worldviews.

-

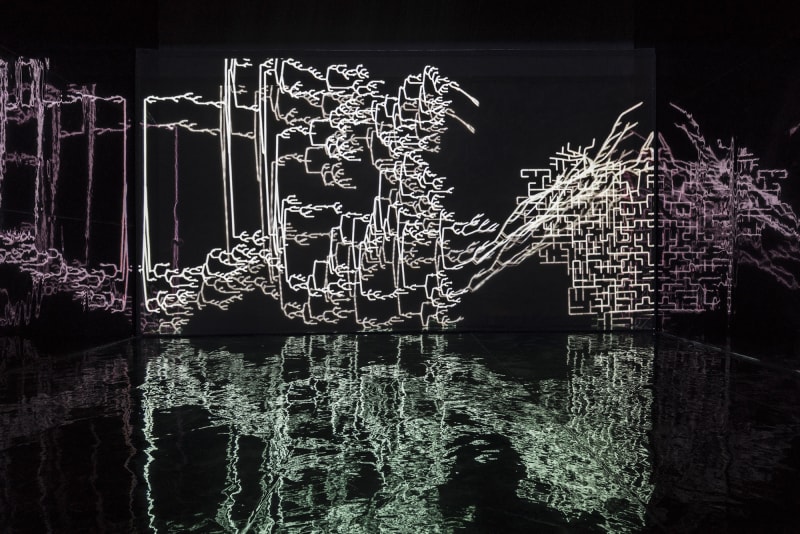

Bingyi 冰逸, The Impossible Landscapes: A Thousand Mountains in One Particle of Dust 不可能的仙山:一尘千山, 2018

Bingyi 冰逸, The Impossible Landscapes: A Thousand Mountains in One Particle of Dust 不可能的仙山:一尘千山, 2018 -

Chen Haiyan 陈海燕, A Peach-Corn Tree on a Mudflat 滩涂上的桃子玉米树, 2010

Chen Haiyan 陈海燕, A Peach-Corn Tree on a Mudflat 滩涂上的桃子玉米树, 2010 -

Huang Zhiyang 黄致阳, Zoon-Beijing Bio: Spring No.1 Zoon-北京生物之春1号, 2013

Huang Zhiyang 黄致阳, Zoon-Beijing Bio: Spring No.1 Zoon-北京生物之春1号, 2013 -

Huang Zhiyang 黄致阳, Zoon-Dreamscape No. 1928 密视 No.1928, 2019

Huang Zhiyang 黄致阳, Zoon-Dreamscape No. 1928 密视 No.1928, 2019 -

Liu Dan 刘丹, Untitled 无题, 2014

Liu Dan 刘丹, Untitled 无题, 2014 -

Li Huasheng 李华生, 0679, 2006

Li Huasheng 李华生, 0679, 2006 -

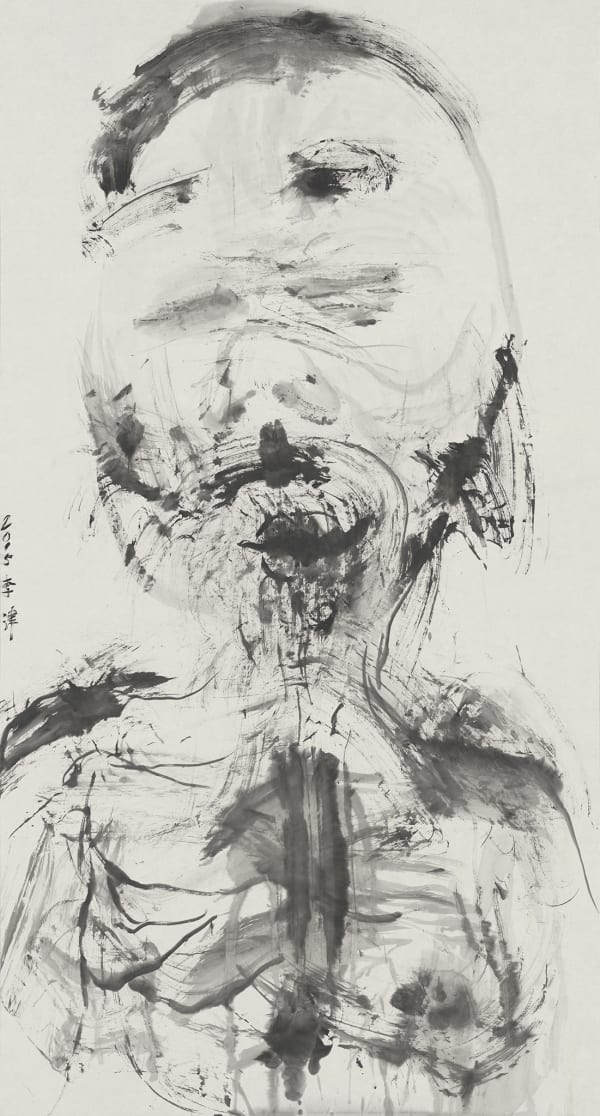

Li Jin 李津, Trance 恍惚, 2015

Li Jin 李津, Trance 恍惚, 2015 -

Li Jin 李津, Unsettled Heart 不定的心, 2015

Li Jin 李津, Unsettled Heart 不定的心, 2015 -

Li Jin 李津, Meat No.5 肉5, 2019

Li Jin 李津, Meat No.5 肉5, 2019 -

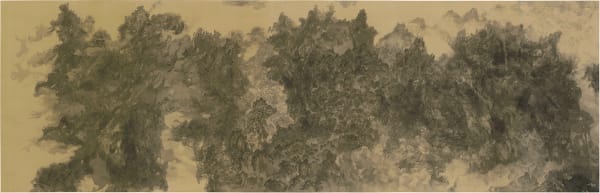

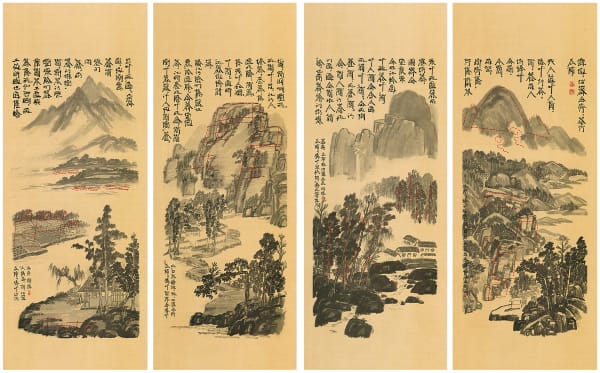

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Voicelss Landscape 山水清音, 2022

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Voicelss Landscape 山水清音, 2022 -

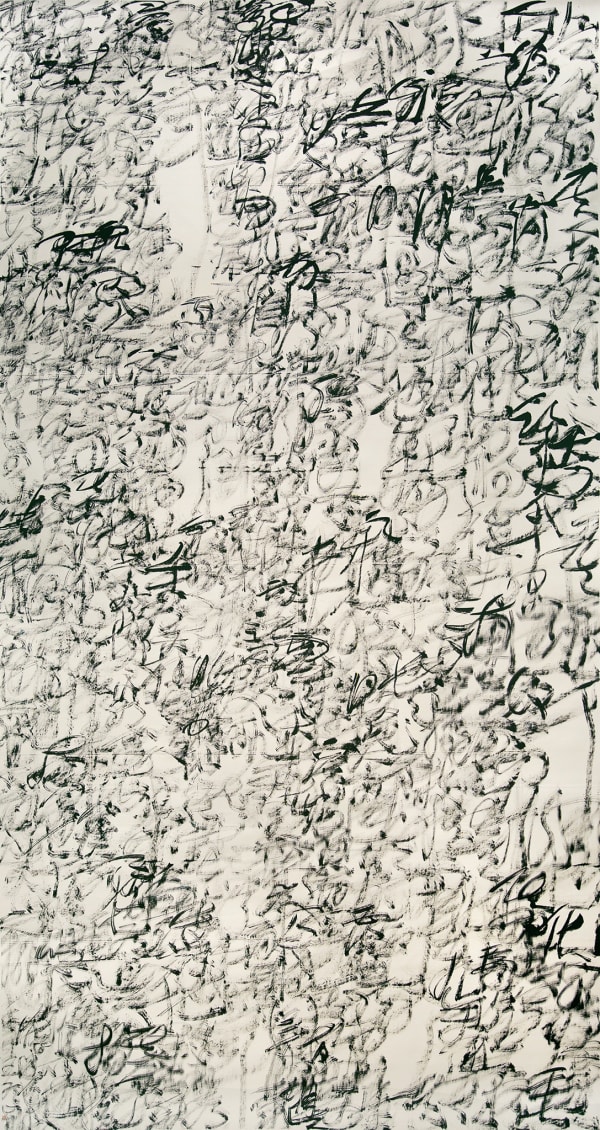

Wang Dongling 王冬龄, Wandering Beyond 逍遥游, 2016

Wang Dongling 王冬龄, Wandering Beyond 逍遥游, 2016 -

Wang Tiande 王天德, Strong Wind Coming through the Snow Cottage 风入雪屋, 2019

Wang Tiande 王天德, Strong Wind Coming through the Snow Cottage 风入雪屋, 2019 -

Wang Tiande 王天德, Thousand Layers of Snow by the Pine Trees 千雪傍松图, 2019

Wang Tiande 王天德, Thousand Layers of Snow by the Pine Trees 千雪傍松图, 2019 -

Xu Bing 徐冰, Suzhou Landscripts 苏州文字写生, 2003-2013

Xu Bing 徐冰, Suzhou Landscripts 苏州文字写生, 2003-2013 -

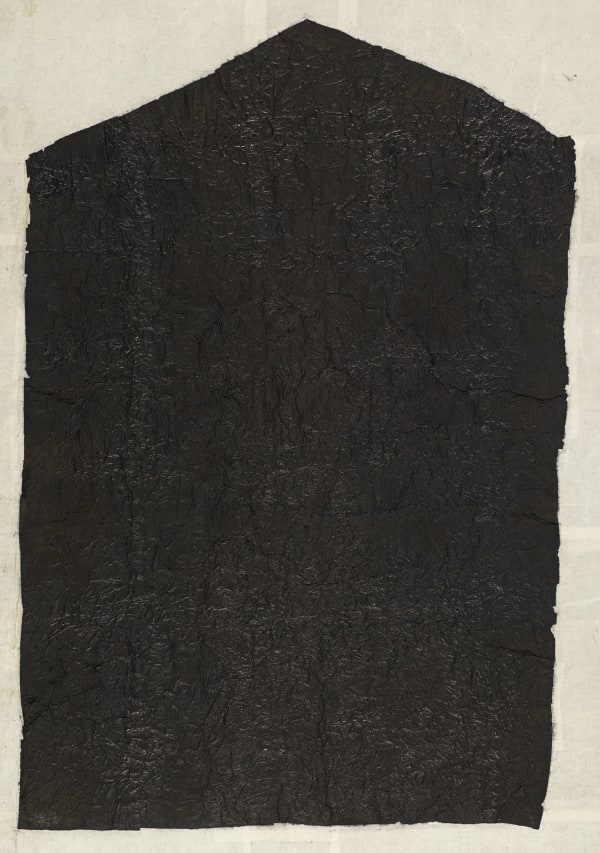

Yang Jiechang 杨诘苍, A Feudal Vassal's Jade Memorial Tablet 诸侯瑹, 1989-1990

Yang Jiechang 杨诘苍, A Feudal Vassal's Jade Memorial Tablet 诸侯瑹, 1989-1990 -

Yang Jiechang 杨诘苍, Traveling in Mexico 墨西哥之旅, 1990

Yang Jiechang 杨诘苍, Traveling in Mexico 墨西哥之旅, 1990 -

Zheng Chongbin 郑重宾, Abrasive Surface 磨擦的表象, 2018

Zheng Chongbin 郑重宾, Abrasive Surface 磨擦的表象, 2018