New York | Many Splendored Spring: The Extraordinary Flower-Landscapes of Peng Kanglong

Ukrainian Institute of America

2 E 79th Street

New York, NY 10075

Peng Kanglong’s Flower-Landscapes

Peng Kanglong彭康隆 (b. 1962 in Hualien, Taiwan) is classically-trained artist who paints in the traditional landscape and flower genres. Landscape and flower painting are two distinct genres with their own metaphoric languages, painting techniques, representative masters and developmental histories. With the possible exception of the Modern master of traditional landscape painting, Huang Binhong (1865–1955), Peng Kanglong is perhaps the first ink artist to explore the artistic possibilities of integrating these formerly separate genres. Whereas Huang Binhong's artistic breakthrough employs the brushwork of flower painting to transform landscape painting, Peng Kanglong works in the reverse direction employing the fine texture strokes and expansive spatial depth of landscape painting to render his extraordinary flower-landscape compositions.

Brushwork, light, spatial depth and negative space are critical to understanding Peng Kanglong's breakthrough. In rendering his flowers, Peng integrates the cunfa or "fine texture strokes" of landscape painting with established shuanggou "outline-and-fill” and mogu "boneless" methods of traditional flower painting. Like landscape texture strokes, Peng's flower texture strokes are based on calligraphy but instead of running or regular script strokes, he employs caoshu or "cursive" and specifically kuangcao or "wild cursive" strokes to render both form and space. These wild cursive texture strokes are not employed in a daxieyi or "boldly calligraphic" expression but rather in a dense and refined, virtuosic performance— brimming with energy but at the most minute and intimate scale.

Peng employs his wild cursive texture strokes to render not only the forms of his trees, flowers and grasses but also the light and space in which his subjects live and breath. Normally in flower painting, this space is left "untouched" or "empty"—liubai and kongbai in classical parlance—but here, Peng fills this empty space with his dense, energetic brushwork. Paradoxically, his paintings still breathe, not with the emptiness of untouched paper but rather with the translucent, luminescent light of his dilute color-and-ink tones. To appreciate Peng's virtuosic brushwork, one must get very close to his works and immerse oneself in the intensity, spontaneity, discipline and utter freedom of his color, ink and line.

Grand Synthesis

Peng Kanglong’s core stylistic influences include the 17th century Monk artists Shitao (1642–1707) and Kuncan (1612 to after 1674), as well as the Modern landscape master Huang Binhong. Beginning in 2020, however, Peng Kanglong undertook an exploration of monumental compositional forms inspired by the Northern Song landscape. This resulted in a series of monumental, horizontal handscroll compositions—including《括囊无咎》Speak and Act Cautiously, 2020 and《含章可贞》Contained Virtues, 2020—which, in turn, culminated in two monumental, vertical compositions—《隆崇赋》Ode to the Mighty Peak, 2022 and《锦绣万花谷》Splendid Flowers Valley, 2022.

Combining the compositional scale of the Imperial landscape of the Northern Song with the expressive, autographic brushwork of the Yuan literati became an artistic goal of landscape painters that followed such as Shen Zhou (1427–1509) and Dong Qichang (1555–1636) of the Ming Dynasty, Wang Hui (1632–1717) and Gong Xian (1618–1689) of the Qing Dynasty and Huang Binhong of the Modern period. What distinguishes Peng Kanglong’s “Grand Synthesis” is his integration not just of composition and brushwork from the Song and Yuan-Ming-Qing periods but his simultaneous cross-integration of the encompassing landscape and flower genres.

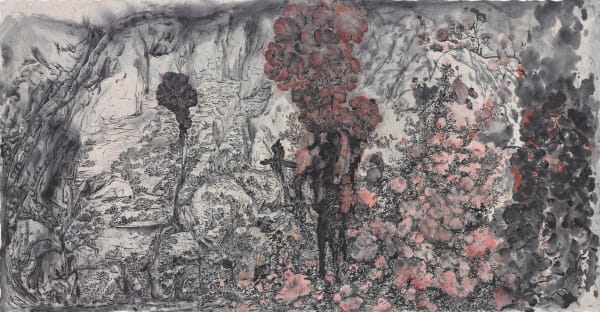

As an example, in his 3.7-meter-high monument《锦绣万花谷》Splendid Flowers Valley from 2022, Peng Kanglong constructs a visually integrated composition consisting of, on the one hand, towering peaks, mountain ridges and recessed river valleys and, on the other hand, precipitous garden rocks amidst blossoming peonies, chrysanthemum and plum, dense grasses and bladed foliage. The artist renders his landscape elements—peaks, ridges, rivers and valleys—in various shades of blue but for his plant and flower elements he employs a variegated palette of reds, pinks, pale greens, golden yellows, black inks and contrasting whites. It is worth noting that Peng renders the two elements that read equally as landscape and flower—the rocky foreground and the vertical garden rock—in emphatic blues and blacks.

To create the illusion of spatial depth, Peng Kanglong eschews the use of a fixed, point perspective and instead employs a moving or shifting perspective. In a shifting perspective, the artist uses different visual strategies to create the illusion of spatial depth from different vantages throughout the composition. The first artist to analyze and articulate these visual strategies was the Northern Song landscape artist Guo Xi (c.1020–c.1090). In his formulation, there were three ways in which an artist could conjure spatial recession based on the way the viewer’s eye moved across the painted surface. In pingyuan or “level distance”, the viewer’s eye moves across a flat, level surface such as a lake, a river valley or a field into deeper recession. In the upper left reaches of Splendid Flowers Valley, Peng Kanglong uses level distance to create a sense of deep recession across high mountain mists to a far horizon. It is worth noting that he uses a similar strategy up close as your eye traverses the rocky foreground that that forms the ground plane of the composition. In shenyuan or “deep distance”, the viewer’s eye moves right or left across a vertical surface or edge such as a cliff or a mountainside into deeper recession. Peng Kanglong uses this visual strategy along the vertical edge of the foreground garden rock and the middle ground mountain ridge as our eye traverses from the right, convex (outward protruding) side of this edge to its left, concave (receding) side. In gaoyuan or “high distance”, the viewer’s eye moves upward from a low point in the composition to a higher point into deeper recession. In Splendid Flowers Valley, Peng Kanglong employs high distance as your eye follows the leftward arching curve from the base of the garden rock (in the foreground) to the mountain ridge arching left (in the middle ground) to mountain peaks receding to the upper right (in the far ground).

It is worth noting that this classic geomantic formation—called a “dragon vein” in the art of fengshui or “geomancy”—Peng Kanglong constructs not just from mountains, ridges and peaks but from garden rocks, foliage and flowers. This strategy creates a spatial paradox: whereas the foreground reads comfortably as a flower and rock garden and the far ground reads intuitively as a landscape in the distance, the middle ground reads at times as garden and at times as landscape and in many places as both at the same time. Spatially, the composition is irrational, paradoxical, impossible—for example, how are we to reconcile at the end of the long curving “dragon vein” the lone peony bloom peeking out from behind its highest-most peak? And yet, somehow, through resonances in brushwork, ink textures, color harmonies and structural movement, Peng Kanglong is able to convince us his part-flower-part-landscape chimeric forms are indeed an integral whole. This tension in depth and distance, between a garden—which we experience up front in relatively shallow depth—and a landscape—which we experience from afar with a sense of deep recession—is unique to Peng Kanglong’s syncretic flower-landscape compositions. Indeed, this new paradoxical juxtaposition, conflation, or mixing of extremely shallow and extremely deep recession extends the spatial possibilities afforded by traditional compositional methods such as Guo Xi’s “Three Distances”.

-

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Splendid Flowers Valley 锦绣万花谷, 2022

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Splendid Flowers Valley 锦绣万花谷, 2022 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Landscape Pulses 山水脉搏, 2022

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Landscape Pulses 山水脉搏, 2022 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Jade Inlaid Vermilion Sky 彤天栽玉, 2022

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Jade Inlaid Vermilion Sky 彤天栽玉, 2022 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Night Flowers at Dawn 日出时的夜花, 2022

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Night Flowers at Dawn 日出时的夜花, 2022 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Frangrant and Flourishing Orchids 幽兰芳霭, 2023

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Frangrant and Flourishing Orchids 幽兰芳霭, 2023 -

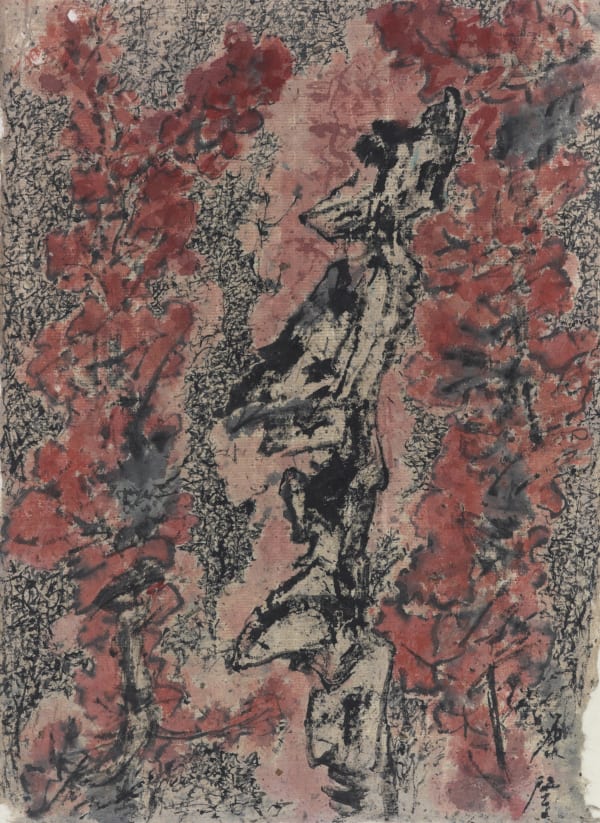

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Elegant and Slender Stems 延颈秀项, 2023

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Elegant and Slender Stems 延颈秀项, 2023 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Black Lingzhi in the Rapids 湍濑玄芝, 2023

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Black Lingzhi in the Rapids 湍濑玄芝, 2023 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Paths of Spring Flowers 烟花径, 2023

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Paths of Spring Flowers 烟花径, 2023 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Facsimile of Flowers 花帖, 2021

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Facsimile of Flowers 花帖, 2021 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, A Pale Autumn 淡淡秋, 2021

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, A Pale Autumn 淡淡秋, 2021 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Blue-green Breath 青息, 2023

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Blue-green Breath 青息, 2023 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Green Rocks 青岩, 2023

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, Green Rocks 青岩, 2023 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, The Withered Poplar Blossoms-2 枯杨生华-2 , 2020

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, The Withered Poplar Blossoms-2 枯杨生华-2 , 2020 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, The Withered Poplar Blossoms-4 枯杨生华-4 , 2020

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, The Withered Poplar Blossoms-4 枯杨生华-4 , 2020 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, The Withered Poplar Blossoms-5 枯杨生华-5 , 2020

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, The Withered Poplar Blossoms-5 枯杨生华-5 , 2020 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, The Withered Poplar Blossoms-6 枯杨生华-6 , 2020

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, The Withered Poplar Blossoms-6 枯杨生华-6 , 2020 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, The Withered Poplar Blossoms-9 枯杨生华-9 , 2020

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, The Withered Poplar Blossoms-9 枯杨生华-9 , 2020 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, The Withered Poplar Blossoms-11 枯楊生華-11 , 2020

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, The Withered Poplar Blossoms-11 枯楊生華-11 , 2020 -

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, The Withered Poplar Blossoms-12 枯杨生华-12 , 2020

Peng Kanglong 彭康隆, The Withered Poplar Blossoms-12 枯杨生华-12 , 2020