b. 1971 in Korea; lives and works in Korea.

Jeong Gwang Hee is a conceptual artist who uses calligraphy, painting, process art and performance art to explore the paradoxical Zen Buddhist use of language and non-language in the soteriological pursuit of enlightenment. A classically trained calligrapher, Jeong Gwang Hee is the latest in a distinguished tradition of East-Asian linguistic-conceptual calligraphers that includes Ruan Yuan (阮元; 1764-1849), Kim Jeong-hui (金正喜; 1786-1856), Mokin Jeon Jongjoo (木人 全钟柱, b. 1951), Suh Se-Ok (徐世鈺; 1929-2020), and Xu Bing (徐冰; b. 1955) amongst others. At the same time, Jeong is a conceptual artist whose focus on language and non-language place him in dialog with language-based Conceptual artists such as Joseph Kosuth (b. 1945) and Lawrence Weiner (1941-2021) as well as anti-language Fluxus artists such as John Cage (1912-1992) and Nam June Paik (1932-2006). However, unlike Kosuth and Weiner who used language to address questions in art, Jeong uses art to address questions of language or, more precisely, meaning beyond language—specifically, the visual semiotics that precede language, insights that follow emancipation from language, the embodied experiences that underlie language, and soteriological methods that supersede language.

Image and Idea: Abstract Image that Precedes Language

In his Thoughts Transcend the Object series (2013-2021), Jeong explores the relationship between image and word and between word and canonical text. He starts with the acquisition of antiquarian books, primarily canonical Confucian, Daoist and Buddhist texts. Jeong disassembles the books, painstakingly mounts and folds the pages and then assembles the folded pages into a vertical surface. Seen on edge, only a of portion of the writing on each page is visible; most of the written content is hidden rendering the text largely unintelligible. Upon this surface, Jeong then paints, with ink and calligraphic brush, what at first appears to be an abstract black form. After prolonged inspection, however, a diagram, graph or image begins to take shape. With some epigraphic sleuthing, this graph resolves into a human eye, set upon two legs, walking down a path and now standing at the four corners of an intersection—Jeong's interpretation of the ancient oracle-bone ideograph for the Chinese character for Dao 道 "the Way" or "discourse."

Unlike in most of the world, where written language is transcribed phonetically using an alphabet or syllabary, in China and much of East Asia, written meaning is conveyed visually with conceptual graphs or characters that can be linked in different linguistic contexts to very different phonetics. The idea that meaning is first captured by abstract images before it is captured in words or language is a fundamental and distinctive aspect of East Asia semiotics recorded as early as the Zhou Dynasty (1050-771 BC) in commentaries on the Yijing otherwise known as the "Book of Changes."

Process and Reflection: Subjective Experience that Underlies Language

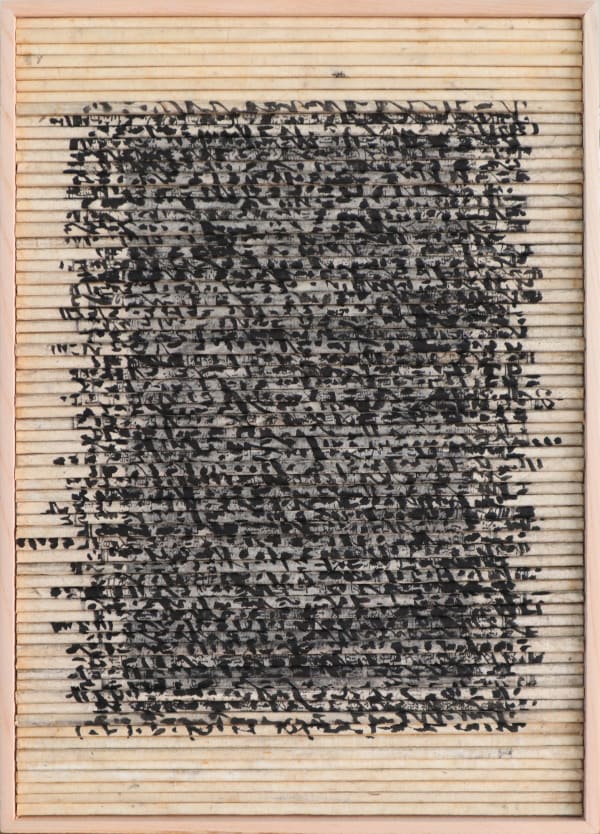

In the series Ja.Ah.Kyung (a scripture reflecting myself)_ Ja.Ah.Kyung (a mirror reflecting) (2016-2021) Jeong again starts with creating a vertical surface for his ink painting made from the folded pages of antiquarian Confucian, Daoist and Buddhist books. This time, before mounting and folding the book pages, Jeong writes in Hangul calligraphy his thoughts and impressions from that day adding on top of the canonical scripture a personal journal entry. When folded and seen on edge, his writing becomes illegible, yet when stacked to form a vertical surface, the shape of a rectangular mirror emerges. To Jeong, the series is a wordless book, "A scripture reflecting myself: a sutra without words … A mirror reflecting: a self-illuminating lamp that illuminates the inner self … The records that show the me who was yesterday is no longer the me who is now." Jeong's mirror metaphor describes meditation as a process of the mind reflecting on itself. Jeong's artistic practice, in turn, is itself a process that trans mediates this internal mental process into an external form that we can all see and experience. For Jeong, the appropriate context for our interpretation of canonical scriptures is our own individual process of self-reflection. Subjective, embodied experience, thus underlies our understanding of scripture making the classics but confirmatory footnotes to one's own lived experience.

Nature and Category: the Insights that Follow Language

In the series of performances Where Will I Spread? (2019-2021), Jeong Gwang Hee starts by creating a shared moment of meditative reflection with his audience. He then silently lifts a traditional white ceramic jar containing pine-soot-based ink and drops it crashing upon the floor where the ink, now released from its shattered container, spreads uncontrolled on a prepared hanji Korean mulberry-paper ground. The white ceramic jar is a metaphor for any structure of containment, control or formal definition. In language one can think of how words are given meaning by conceptual category. Dropping the jar is an act of release by the artist that results in the breaking of the container. In Buddhist teachings and particularly Zen practice, sudden enlightenment into the nature of pure experience becomes possible when we liberate ourselves from the illusions generated by categorical thought. The subsequent spreading of the ink evokes the state of pure nature that comes after we liberate ourselves from the controlling, conceptual limitations that language places on our experience. For Jeong, this is not just an individual experience, but a collective one. If indeed language is the collective endeavor of a community of speakers, then Jeong's performance of liberation from language is a wish for sudden collective insight. And the question "Where Will I Spread?" becomes a question not just for us as individuals but for us as a society.

Soteriology: the Methods that Supersede Language

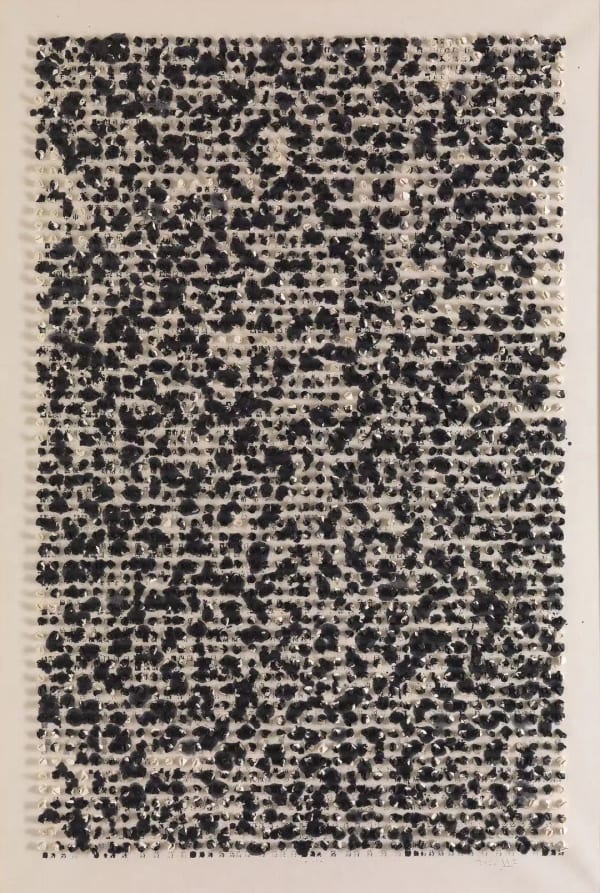

In the series The Way of Reflection series (2017-2021) Jeong combines the sudden release from Where Will I Spread with the gradual process of reflection of from Ja.Ah.Kyung (a scripture reflecting myself)_ Ja.Ah.Kyung (a mirror reflecting). Here, Jeong rolls hanji paper into small balls by hand and then dips them into ink in a partly-controlled, partly-uncontrolled process analogous to the controlled shattering and uncontrolled spreading of ink in Where Will I Spread. Jeong then attaches the hundreds of ink-glazed paper balls one-at-a-time onto a blank sheet of hanji paper in a rectangular grid analogous to written characters on a printed page. In this way, Jeong makes liberation from conceptual category a repeated meditative process and thereby integrates into a coherent visual whole what in Buddhist practice would be called sudden and gradual enlightenment.

The visual patterns that emerge from the interplay of black and white, substance and emptiness, sudden and gradual, process and form, are evocative of another hermeneutic tradition. Specifically, Jeong's arrays of wadded and inked hanji balls are like the broken and unbroken yin and yang lines in a Yijing hexagram. Jeong's arrays, however, are vastly more complex than an Yijing hexagram; whereas a hexagram, as its name indicates, has only six possible alternations, only one of Jeong's arrays can encompass hundreds. It is worth noting that the Yijing or Book of Changes is a Confucian and a Taoist classic, whereas the Platform Sutra (ca. 8th Century)—where the principles of sudden and gradual enlightenment are most clearly expounded—is a Zen Buddhist classic. The Way of Reflection thus posits a non-linguistic soteriological method—a practice that leads to enlightenment—that unites these two canonical texts while, at the same the time, superseding them.

Jeong Gwang Hee's works have been exhibited at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles (2021), the Jeonnam International SUMUK Biennale, Mokpo, Korea (2019), PLATFORM, Munich, Germany (2019), the MOCA Yinchuan, Yinchuan, China (2017), the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Art Museum, Guangzhou, China (2016), the National Art Museum of China, Beijing (2015), the Himalaya Museum of Art, Shanghai (2014), the Gwangju Museum of Art, Gwangju, Korea (2014, 2011, 2010), the Shandong Museum, Jinan, China (2013), and the Busan Museum of Art, Busan, Korea (2010). His works have been collected by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, USA, the Gwangju Museum of Art, Gwangju, Korea, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea, the Take a Step Back Collection, Hong Kong SAR, and Fondation INK, Geneva, Switzerland.

-

The Way of Reflection No. 15, 2021

The Way of Reflection No. 15, 2021 -

Thoughts Transcend the Object 思想超脱对象, 2021

Thoughts Transcend the Object 思想超脱对象, 2021 -

Where Will I Spread, 2021

Where Will I Spread, 2021 -

The Way of Reflection No. 10, 2020

The Way of Reflection No. 10, 2020 -

The Way of Reflection No. 8, 2020

The Way of Reflection No. 8, 2020 -

Ja.Ah.Kyung(a scripture reflecting myself)_ Ja.Ah.Kyung(a mirror reflecting) 自我经-自我镜, 2016-2019

Ja.Ah.Kyung(a scripture reflecting myself)_ Ja.Ah.Kyung(a mirror reflecting) 自我经-自我镜, 2016-2019 -

Ja.Ah.Kyung(a scripture reflecting myself)_ Ja.Ah.Kyung(a mirror reflecting) 自我经-自我镜, 2016-2019

Ja.Ah.Kyung(a scripture reflecting myself)_ Ja.Ah.Kyung(a mirror reflecting) 自我经-自我镜, 2016-2019 -

Ja.Ah.Kyung(a scripture reflecting myself)_ Ja.Ah.Kyung(a mirror reflecting) 自我经-自我镜, 2016-2019

Ja.Ah.Kyung(a scripture reflecting myself)_ Ja.Ah.Kyung(a mirror reflecting) 自我经-自我镜, 2016-2019 -

Reflection III 映 III, 2016

Reflection III 映 III, 2016 -

Life 1, 2013

Life 1, 2013

-

Taipei | Contemporary Ink, Global context

Bingyi, Jeong Gwang Hee, Li Huasheng, Jennifer Wen Ma, Wang Tiande, Yang Jiechang, Zheng Chonbin 18 - 24 Oct 2023Virtual Exhibition INKstudio is delighted to present the exhibition 'Global Ink, Contemporary Contexts' in Taipei. INKstudio selected seven artists based in various regions across continents, including Western Europe, the United...Read more -

One Breath – Infinite Vision

Choi Ildan & Cho Duck Hyun & Jeong Gwang Hee & Kim Ho Deuk & Kim Jongku & Lee In & Lim Hyun Lak & Lim Oksang & Ahn SungKeum 21 Sep - 3 Nov 2019INK studio Beijing is pleased to present One Breath–Infinite Vision, an exhibition of Korean ink art curated by Yu Yeon Kim.Read more

The exhibition includes twenty-six works by nine Korean artists, Choi Ildan, Cho Duck Hyun, Jeong Gwang Hee, Kim Ho Deuk, Kim Jongku, Lee In, Lim Hyun Lak, Lim Oksang, and Ahn SungKeum.

-

INKstudio at West Bund 2021

Jeong Gwang Hee, Lee In, Li Huasheng, Wang Dongling, Wang Tiande November 6, 2021BOOTH A212 11-14. 11, 2021 West Bund Art Center, Building A INKstudio will explore INK as the basis for an international contemporary art rooted in...Read more -

Opening Oct 23|The Inauguration of Blanc International Contemporary Art Space

October 20, 2021Exhibition Period October 23, 2021 - January 23, 2022 (Closed on Mondays, opening on holidays) Public opening hours: 10:00-18:00 Blanc International Contemporary Art Space, Building...Read more